From International Standard Bible Encyclopedia

Babylon baʹbə-lon; BABEL bāʹbəl (Gen. 10:10; 11:9) [Heb bābel—‘gate of god’; Akk bāb–ili, bāb-ilāni—‘gate of god(s)’; Gk Babylōn; Pers Babirush]. The capital city of Babylonia.

Location

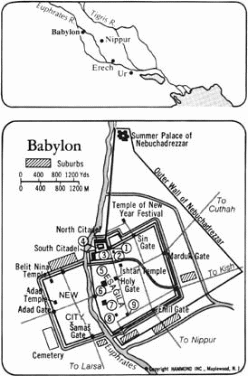

Babylon lay on the bank of the Euphrates in the land of Shinar (Gen. 10:10), in the northern area of Babylonia (now southern Iraq) called Accad (as opposed to the southern area called Sumer). Its ruins, covering 2100 acres (890 hectares), lie about 50 mi (80 km) S of Baghdad and 5 mi 8 (km) N of Hillah. The ancient site is now marked by the mounds of Bâbil to the north, Qaṣr (“the Citadel”) in the center, and Merkes, ‘Amran Ibn ‘Alī Ṣaḥn, and Homera to the south. The high water and long flooding of the whole area render the earlier and lower ruins inaccessible.

Name

The oldest attested extrabiblical name is the Sumerian ká-dingir-ki (usually written ká-dingir-ra, “gate of god”). This may have been atranslation of the more commonly used later Babylonian Bāb-ilī, of which an etymology based on Heb bālal, “confused,” is given in Gen 11:9. Throughout the OT and NT, Babylon stands theologically for the community that is anti-God. Rarely from 2100 b.c. and frequently in the 7th cent Babylon is called TIN.TIR.KI, “wood (trees) of life,” and from the latter period also. E.KI, “canal zone (?).” Other names applied to at least part of the city were ŠU.AN.NA, “hand of heaven” or “high-walled (?),” and the Heb šēšaḵ (Jer. 25:26; 51:41), which is usually interpreted as a coded form (Athbash) by which š = b, etc. The proposed equation with ŠEŠ.KU in a late king list has been questioned, since this could be read equally well as (É).URU.KU.

Early History

A. Foundation Genesis ascribes the foundation of the city to Nimrod prior to his building of Erech (ancient Uruk, modern Warka) and Accad (Agade), which can be dated to the 4th and 3rd millennia b.c. respectively. The earliest written reference extant is by Šar-kali-šarri of Agade ca 2250 b.c., who claimed to have (re)built the temple of Anunītum and carried out other restorations, thus indicating an earlier foundation. A later omen text states that Sargon (Šarrukīn I) of Agade (ca 2300) had plundered the city.

B. Old Babylonian Period Šulgi of Ur captured Babylon and placed there his governor (ensi), Itur-ilu, a practice followed by his successors in the Ur III Dynasty (ca [5 highlights]2150–2050 [5 highlights]b.c.). Thereafter invading Semites, the Amorites of the 1st Dynasty of Babylon, took over the city. Their first ruler Sumu-abum restored the city wall. Though few remains of this time survive the inundation of the river, Hammurabi in the Prologue to his laws (ca 1750) recalls how he had maintained Esagila (the temple of Marduk), which by the time of his reign was the center of a powerful regime with wide influence. Samsu-iluna enlarged the city, but already in his reign the Kassites were pressing in from the northeast hills. It actually fell in 1595 to Hittite raiders under Mursilis I, who removed the statue of Marduk and his consort Ṣarpānītum to Ḫana. (Possession of a city’s gods [their statues] symbolized control.) The city changed hands frequently under the Kassites (Meli-Šipak [Meli-Šiḫu] and Marduk-aplaiddina I) amid the rivalry of the local tribes. Agumkakrime recovered the captive statues, but that of Marduk was again removed at the sack of the city by Tukulti-Ninurta I of Assyria (1250) and by the Elamite Kudur-Naḫḫunte II (1176).

C. Middle Babylonian Period The recovery of Marduk’s statue was the crowning achievement of Nebuchadrezzar I (1124–1103), marking an end to foreign domination of the city. He restored it to Esagila amid much public rejoicing and refurbished the cult places. Although Babylon retained its independence despite the pressure of the western tribes, this required help from the Assyrians, one of whom, Adad-apal-iddina, was given the throne (1067–1046). By the following century, however, the tribesmen held the suburbs and even prevented the celebration of the New Year Festival by Nabû-mukīn-apli of the 8th Babylonian Dynasty.

D. Neo-Assyrian Supremacy Shalmaneser III of Assyria was called to intervene in the strife that broke out on the death of Nabû-apla-iddina in 852 b.c. He defeated the rebels, entered Babylon, treated the inhabitants with respect, and offered sacrifices in Marduk’s temple. This action inaugurated a new period of Assyrian intervention in the southern capital, with the result, according to Herodotus, that Sammu-ramat (Semiramis), mother of Adadnirari III, carried out restoration work there.

The citizens’ independent spirit was never long suppressed; and Arameans from the southern tribes seized the city, made Erība-Marduk their leader, and refused to pay allegiance to the northern kingdom. To remedy this Tiglath-pileser III began a series of campaigns to recover control. First he won over the tribe of Puqūdu (Pekod of Jer. 50:21; Ezk. 23:23), who lived to the northeast, leaving Nabonassar (Nabû-nāṣir) as governor of Babylon to pursue a pro-Assyrian policy until his death in 734 [5 highlights]b.c., whereupon Ukīn-zēr of the Amukkani tribe seized the city.

The Assyrians then tried to gain the support of the other tribal chiefs, including Marduk-apla-iddina (Merodach-baladan of the OT) of Bīt-Yakin, who, however, took over the city on the death of Tiglath-pileser’s successor Shalmaneser V in 721. He proclaimed the city’s independence and maintained it for ten years. Either toward the end of this period or more probably in 703 b.c., when he again held Babylon, Merodach-baladan sought Hezekiah’s help against the Assyrians (2 K. 20:12–17). Sargon II recaptured the city in 710 and celebrated the New Year festival by taking the hands of Marduk/Bēl and the title “viceroy of Marduk.”

To revenge Merodach-baladan’s later seizure of the capital, Sennacherib marched south to remove the traitor Bēl-ibni and set his own son Aššur-nadin-šumi on the throne. The latter was soon ousted, however, by local revolutionaries, who in turn were defeated by Sennacherib in 689 when he besieged the city for nine months, sacked Babylon, and removed the statue of Marduk and some of the sacred soil to Nineveh. Though this act brought peace, it broke any trust the citizens ever had in the Assyrians, despite Esarhaddon’s efforts to restore the decrepit town. Esarhaddon claimed to have revoked his father’s decree imposing “seventy years of desolation upon the city” by reversing the Babylonian numerals for 70 to make them 11. Many refugees returned, and the city again became a prosperous center under his son Šamaš-šum-ukīn (669–648). He was isolated, however, by the surrounding tribes, who eventually won him over to their cause. His twin brother Ashurbanipal of Assyria laid siege to the city, which fell after four years of great hardship. Šamaš-šum-ukīn died in the fire that destroyed his palace and the citadel.

E. Chaldean Rulers Reconstruction work began under the Chaldean Nabopolassar (Nabû-apla-uṣur, 626–605 [5 highlights] b.c.), who was elected king following a popular revolt after the death of the Assyrian nominee Kandalanu. His energetic son Nebuchadrezzar (II) with his queen Nitocris restored not only the political prestige of Babylonia, which for a time dominated the whole of the former Assyrian empire, but also the capital city, to which he brought the spoils of war including the treasures of Jerusalem and Judah (2 K 25:13–17). Texts dated to this reign list Jehoiachin king of Judah (Ya’ukin māt Yaḫudu), his five sons, and Judean craftsmen among recipients of corn and oil from the king’s stores. It is to the city of this period, one of the glories of the ancient world, that the extant texts and archeological remains bear witness. Nabonidus (555–539 [5 highlights]b.c.) continued to care for the temples of the city, though he spent ten years in Arabia, leaving control of local affairs in the hands of his son and co-regent Belshazzar, who died when the city fell to the Persians in 539 (Dnl 5:30).

Description

A. Walls Babylon lay in a plain, encircled by double walls. The inner rampart (dūru), called “Imgur-Enlil,” was constructed of mud brick 6.50 m (21 ft) thick. It had large towers at intervals of 18 m (60 ft) jutting out about 3.5 and.75 m (11.5 and 2.5 ft) and rising to 10–18 m (30–60 ft). It has been estimated that there were at least a hundred of these. The line may well have followed that laid down by Sumu-abum of the 1st Dynasty. Over 7 m (23 ft) away lay the lower and double outer wall (šalḫu) called Nimit-Enlil, 3.7 m (12 ft) thick, giving a total defense depth of 17.4 m (57 ft). Twenty m (65 ft) outside these walls lay a moat, widest to the east and linked with the Euphrates to the north and south of the city, thus assuring both river passage and water supply and a flood defense in time of war. The quay wall nearest the city was of burnt brick set in bitumen, and this too had observation towers. The outermost wall of the moat was of beaten earth. The inner area, including Babylon W of the river, which remains unexcavated, measured 8.35 sq km (3.2 sq mi) and the eastern city alone encompassed an area of about 2.25 sq km (.87 sq mi). Nebuchadrezzar and, according to Herodotus, his queen Nitocris made significant additions to the defenses begun by his father. These now incorporated his “Summer Palace” (Bâbīl) 2 km (1.2 mi) to the north. He also added an enlarged northern citadel and enclosed a large area of the plain with yet a third wall, forming an “armed camp” in which the surrounding population could take refuge in time of war. This ran 250 m (820 ft) S of the inner walls and projected about 1.5 km (1 mi) beyond the earlier wall systems.

Herodotus, who describes the city and walls some seventy years after the damage done by Xerxes in 478 b.c. (i.178–187), appears to exaggerate the size. He says that the height of the walls, beyond the moat, was 200 cubits (about 90 m or 300 ft) by 50 royal cubits thick (= 87 ft, 26.5 m). The width was sufficient for a chariot and four horses to pass along them. Moreover, the estimate of the total length of the walls as 480 stades (about 95 km or 60 mi) is difficult to reconcile with the archeological evidence, though the figures are close to those given by Ctesias (300 furlongs = 68 km or 42 mi, with the walls 300 ft [90 m] high and 60, 40, and 20 furlongs in length respectively). Herodotus viewed the city as a rectangle. Unfortunately no excavations to confirm this have yet been possible West of the river.

B. Gates Babylonian inscriptions give the names of the eight major entrances to the city itself, but of these only four have been excavated. The southwest gate of Uraš was probably typical in general plan. The approach was by a dam across the moat through a wide gateway in the outer wall with recessed tower chambers and thence by a deep gateway in the inner wall. The other gate in the south wall was named after Enlil, since it faced southeasterly toward his sanctuary at Nippur. In the east wall were the gate called “Marduk is merciful to his friend” and, S of this, the Zababa gate facing Kish. In the north wall the Ishtar gate was specially decorated and renovated by Nebuchadrezzar at the time of his enlargement of the citadel.

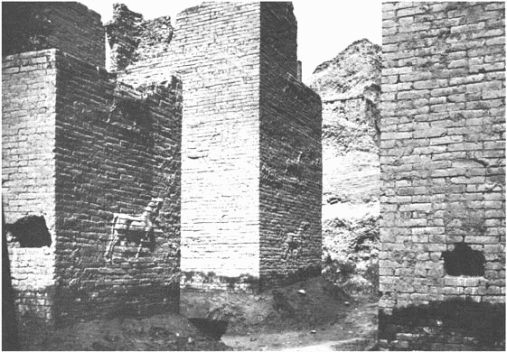

The Sin gate in the north wall and the Šamaš and Adad gates in the west are known only from references in the texts. These gates may well be identified with the five named by Herodotus as Semiramis (Ishtar), Nineveh (Sin to the north?), Chaldean (Enlil? to the south), Kissian (Zababa), and Zeus Belos (Marduk). He further mentions one hundred gates of bronze in the outer walls, which may be “the well-built wide gates with doors of bronze-covered cedar” made by Nebuchadrezzar. Excavations show that the Ishtar gate consisted of a double tower 12 m (40 ft) high, decorated with blue and black glazed bricks with alternate rows in yellow relief of 575 mušruššu (a symbol of Marduk, a combination of a serpent with lion’s and eagle’s legs) and the bulls of (H)adad.

C. Streets The layout of the principal streets was determined by the line of the river and of the main gates and was virtually unchanged from Old Babylonian times. The main thoroughfare, called Ai-ibūr-šābū (“the enemy shall not prevail”), was the sacred procession way running from the Ishtar gate SSE, parallel with the Euphrates. Completed by Nebuchadrezzar, it ran for more than 900 m to the temple Esagila before joining the main east-west road between that temple and the sacred area of Etemenanki and then turning to the Nabonidus wall on the river. There the crossing was made by a stone bridge, 6 m wide, supported by eight piers, each 9 by 21 m (29 by 69 ft), the six amid stream being of burnt bricks that still show traces of wearing by the current. The bridge was 123 m (403 ft) long, shortened to 115 m (377 ft) when Nabonidus built his quay. Herodotus ascribed the bridge to Nitocris (i.186; cf. Diodorus ii.8) and speaks of it as an “open bridge,” perhaps with a removable center section to enable the two parts of the city to be defended independently.

The Procession Way was 11–20 m (36–66 ft) broad and paved with colored stone from Lebanon, red breccia, and limestone. Some paving stones were inscribed “I Nebuchadrezzar, king of Babylon, paved this road with mountainstone for the procession of Marduk, my lord. May Marduk my Lord grant me eternal life.” The parapet of the raised road was decorated with 120 lions in relief.

The other main roads intersected the city at right angles and bore names associated with the gates from which they led: “Adad has guarded the life of the people”; “Enlil establisher of kingship”; “Marduk is shepherd of his land”; “Ishtar is the guardian of the folk”; “Šamaš has made firm the foundation of my people”; “Sin is stablisher of the crown of his kingdom”; “Uraš is judge of his people”; and “Zababa destroys his foes.” There were also other procession streets named after deities — Marduk (“Marduk hears him who seeks him”) and Sibitti — and also after earlier kings (Damiq-ilišu).

D. Citadel The northern wall was extended in the center by Nebuchadrezzar to form an additional defense for the palaces to the south and to provide more accommodation. This complex appears to have been used by his successors as a storehouse (some think as a “museum”), for here were found objects from earlier reigns including inscriptions of the Assyrian kings Adadnirari III and Ashurbanipal from Nineveh, a Hittite basalt sculpture of a lion trampling a man (“the lion of Babylon”), and a stele showing the Hittite storm-god Tešub from seventh-century (b.c.) Sam’al.

E. Palaces In the southern citadel, bounded by the Imgur-Enlil wall (N), the river (W), the Procession Way (E), and the Libilḫegalla canal (which was cleared by Nebuchadrezzar and linked the Euphrates and the Banitu canal E of the city with the canal network in the New City, thus providing the city with a system of internal waterways), was a massive complex of buildings covering more than 360 by 180 m (400 by 200 yds). Here lay the vast palace built by Nabopolassar and extended by his successors. The entrance from the Procession Way led to a courtyard (66.5 by 42.5 m, 218 by 140 ft), flanked by quarters for the royal bodyguard, which in Nebuchadrezzar’s time largely consisted of foreign mercenaries. A double gateway led into the second court, off which lay reception rooms and living quarters. A wider doorway gave access to a third court (66 by 55 m, 218 by 180 ft); to its south lay the Throne Room, the external wall of which was decorated in blue glazed bricks bearing white and yellow palmettes, pillars with a dado of rosettes and lions. This large hall (52 by 17 m, 170 by 57 ft, partially restored in 1968) could have been that used for state occasions, such as Belshazzar’s feast for a thousand persons (Dnl. 5). Two further wings of the palace overlooking the river to the west may have been the quarters of the king, his queen, and their personal attendants. It is more likely that this was the building used by Belshazzar for his feast rather than the “Palace of the Crown Prince” (ekal mār šarri) said to have been used later by Xerxes.

In the northwest angle of this complex, adjacent to the Ishtar gate, lay another large building (42 by 30 m, 140 by 98 ft) consisting of fourteen narrow rooms leading off a long central walk. Since it was at some time walled off from the new palace, it has been thought to have been the substructure of that wonder of the ancient world, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. According to Ctesias in Diodorus (ii.10) and Strabo (xvi.1.5), this was a series of garden-laid terraces supported by arches designed by Nebuchadrezzar (so Berossus in Josephus Ant. x.11.1 [226]) for his queen, to remind his new bride, Amyitis daughter of Astyages the Mede, of her mountain-fringed homeland. This description might, however, equally apply to the ziggurat (see G below).

The presence of administrative texts within these subterranean rooms more likely indicates that these were palace stores. Included among the tablets found here and dated to the tenth to thirty-fifth years of Nebuchadrezzar (i.e., 595–570 [5 highlights]b.c.) were lists of recipients of rations of corn and oil distributed to foreigners, men from Judah, Ashkelon, Gebal, Egypt, Cilicia, Greece (Yamanu), and Persia. Among the men of Judah were Jehoiachin and his sons and craftsmen, some with such OT names as Gaddiel, Shelemiah, and Samakiah (E. F. Weidner, Mélanges offerts à M. Dussaud, II [1939], 924ff). Nebuchadrezzar also built himself a “Summer Palace” outside the main citadel but within the defense walls. This was set 9 m (30 ft) high (it was 100 m [328 ft] long) to catch the cooler northeast winds.

F. City Quarters Tablets name the various parts of the city, which included the citadel itself (ālu libbi āli, “city within a city”) with at least nine temples. It was described as near ká-dingir-ra, which name also applied to the whole city. The citadel included the royal palace as far as Esagila. Here were to be found the temples of Ishtar and Ninmaḫ. Other quarters were named Kaṣiri, Kullab, and Kumari. The “New City” (ālu eššu) lay on the west bank of the Euphrates and was part of the Chaldean extension. Large areas within the city walls were given up to parks and squares.

G. Temple Tower (Ziggurat) The ziggurat of Babylon, É-temen-an-ki (“building [of] the foundation of heaven and earth”), lay in the center of the city, S of the citadel, now marked by the ruin-area Ṣaḥn (“the Pan”), a deep depression near the mausoleum of ‘Amrān Ibn ‘Alī founded a.d. 680. It lay in a square doublecasemate walled enclosure, forming a rectangular courtyard measuring about 420 by 375 m (460 by 410 yds). Entry was by two doors in the north and ten elaborate gateways. The enclosure was frequently repaired, and bricks marking this activity in the reign of Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal of Assyria and of Nebuchadrezzar have survived. The area was subdivided into a long narrow western court, a northern court in which towered the ziggurat with its adjacent monumental buildings, wall shelters for the pilgrims, housing for the priests, and storerooms. The main approach from the Procession Way led between two long storerooms. One late Babylonian text, the Esagila tablet AO 6555, gives the dimensions of the courts and the names of the gates: “grand”; “the rising sun”; “the great gate”; “gate of the guardian colossi”; “canal-gate”; and “gate of the tower-view.”

Opposite the main gate lay the stepped tower on a platform with shrines grouped around. The stages are given as 91 m sq by 34 m high (300 ft sq by 110 ft high) for the lowest, the next 80 m sq by 18 m high (260 ft sq by 60 ft high), the next three diminishing stages each 6 m (20 ft) high and 61, 52, and 43 m (200, 170, and 140 ft) square. Originally each stage, as at Ur, may have been of different color. The sanctuary of Marduk (Bēl) on top, 15 m (50 ft) high, gave a total height of 85 m (280 ft). However, nothing remains of the tower except the lower stairs, the whole having been plundered for its bricks by local villagers. There is no reason to doubt the identification of this site with the Tower of Babel (Gen. 11:1–11), the building of which had been terminated. The inscriptions refer only to rebuilding and repair work by the later kings of Babylon. The common identification of the Tower of Babel with the remains of the ziggurat at Borsippa, 7 mi (11 km) SSW, is open to question on a number of grounds, not the least that that edifice was in a separate city. The extant vitrified ruins there are of a temple tower also rebuilt by Nebuchadrezzar II.

Herodotus (i.181–183) described Etemenanki, which he called the “sanctuary” of Zeus Belos. It was, he wrote, 2 stadia sq and was entered through a bronze gate. The temple tower stood in the center of the sanctuary, its sides 1 stadium (200 m, 650 ft) long, with eight towers, one on top of the other. It also had slopes or steps rising on each level. (See Babel, Tower Of.) In the large topmost temple was a couch covered in beautiful rugs with a golden table. There was no image of the deity, and the Chaldean priests informed Herodotus that one unmarried native woman spent the night there to be visited by the deity. Though Herodotus did not believe the story, it conforms to the known Babylonian view of the sacred marriage.

H. Esagila The principal temple of Babylon, Esagila (“house of the uplifted head”), was dedicated to the patron deity of the city Marduk. It lay S of Etemenanki, which must have overshadowed it. The excavations by Koldewey in the ‘Amrān Ibn ‘Alī mound disclosed sufficient evidence to recover the ground plan of two building complexes. The main shrine to the west (10 by 79 m, 33 by 260 ft) was entered by four doors, one on each side. At a lower level than the principal shrine, that of Marduk, were chapels and niches for lesser deities around the central courtyard. Nabopolassar claimed to have redecorated the Marduk shrine with gypsum and silver alloy, which Nebuchadrezzar replaced with fine gold. The walls were studded with precious stones set in gold plate, and stone and lapis lazuli pillars supported cedar roof beams. The texts describe the god’s gilded bedchamber adjacent to the throne room.

Herodotus (i.183) described two statues of the god, one seated. The larger was said to be 12 ells (6 m, 20 ft) high, but Herodotus did not see it, being told that it had been carried off by Xerxes. This was the usual practice of those kings who wished to curb the independent citizens of Babylon. The opposite action, that of “taking the hand of Bēl (Marduk)” to lead the statue out of the akitu (New Year) house and into Esagila, ensured their authority and usually acceptance by the people. Herodotus was told that 800 talents (16.8 metric tons) of gold were used for these statues and for the table, throne, and footstool. A thousand talents of incense were burned annually at the festivals while innumerable sacrificial animals were brought in to the two golden altars, one used for large, the other for small victims.

Esagila was first mentioned by Šulgi of Ur, who restored it ca 2100 b.c. Sabium, Hammurabi, Samsuiluna, Ammi-ditana, Ammi-ṣaduqa and Samsu-ditana all refer to their devotion to the temple during the 1st Dynasty of Babylon (1894–1595), a care that was to be continued by every king and conqueror of Babylon except Sennacherib. Some refer to their dedications to Marduk and Ṣarpānītum or to Nabû and Tašmetum in their twin shrine at Ezida (“house of knowledge”). One of the best-known of these votive gifts was the diorite stele engraved with the laws of Hammurabi and set up in Esagila as a record of the manner in which that king had exercised justice. The standard brick inscription of Nebuchadrezzar describes him as “provider for Esagila and Ezida.” At a lower level in Esagila were located the shrines of Ea to the north, Anu to the south, and elsewhere Nusku and Sin. To the east of Esagila lay a further complex of buildings (89 by 116 m, 292 by 380 ft) the precise purpose of which is not known.

I. Other Temples In addition to Ezida, Babylonian texts refer to at least fifty other temples by name, Nebuchadrezzar himself claiming to have built fifteen of them within the city. Excavations have uncovered the temple of Ishtar of Agade (Emašdari) in the area of private houses (Merkes), E of the Procession Way. This faced toward the southwest and was rectangular in form (37 by 31 m, 111 by 102 ft) with two entrances, S and E, leading into an inner court. The plan was similar to others of the period (e.g., Ezida of Borsippa) with six antechambers alongside the antechapel and shrine, which led directly off the court. This temple was kept in order by Nebuchadrezzar and Nabonidus and lasted into the Persian era.

Koldewey also cleared two temples E of ‘Amrān Ibn ‘Alī in the Išin-Aswad mound. One cannot be identified as yet due to the absence of inscriptions, hence its designation “Z” temple. This was in continual use over at least seventeen hundred years. To the east lay the shrine of Ninurta (Epatitilla, “temple of the staff of life”) built by Nabopolassar, according to its foundation cylinder. This was restored by Nebuchadrezzar. Here the plan (190 by 133 m, 623 by 436 ft) differs, the main entry being to the east, with subsidiary doors to the north and south. Off the courtyard to the west lay three interconnected equal shrines, each with a dais perhaps dedicated to Ninurta and his wife Gula and son Nusku.

Near the Ishtar gate stood the well-preserved temple of Ninmaḫ, goddess of the underworld, constructed by Ashurbanipal ca 646 b.c. Outside this massive building, called Emaḫ, stood an altar. Passing this to the main door on the north side, worshipers would then traverse the courtyard, passing a well, to enter the shrine in the antechapel. Here they would kneel before the statue of the goddess splendidly clothed and standing on its dais. The architect, Labāši, had designed the surrounding storerooms with a view to security, since many valuable votive offerings must have been hoarded there together with the many fertility figurines found in them. The outer wall was defended by towers, since the shrine may have lain outside the main city defenses. This building has now been fully restored by the Iraqi Department of Antiquities. The cuneiform texts imply that there were many shrines in the city, “180 open-air shrines for Ishtar” and “300 daises for the Igigi gods and 1200 daises of the Anunnaki gods.” There were also more than two hundred pedestals for other deities mentioned. The open-air shrines were probably similar to those for the intercessory Lama goddess found at crossroads at Ur.

J. Private Houses A series of mounds to the north of Išin Aswad at Babylon are called locally Merkes, “trade center.” Since the levels containing houses were easier to excavate, being on raised ground, it was possible for Koldewey to trace occupation here almost continuously from the Old Babylonian period to the Parthian period. Here too the streets ran almost straight and crossed at right angles. The houses consisted of a series of rooms around a central courtyard. They were made of mud brick roofed with mats set over wooden beams, and many showed signs of the fire that had raged in the destruction of the city at the hands of the Hittites, Sennacherib, or Xerxes. Several of the buildings had foundation walls 1.8 m (6 ft) thick; and, like “the Great House” in Merkes, this may indicate that they supported more than one story. Nevertheless, Herodotus’ observation that “the city was filled with houses of three or four stories” cannot now be checked. Some houses may have been built on higher ground than others. Moreover, his expression órophos could be rendered “roofs” rather than “story.”

K. Documents Apart from the architectural remains, the decorations of the Ishtar gate, and small objects, the most significant finds from ancient Babylon are more than thirty thousand inscribed tablets. Since apart from the Merkes the Old Babylonian levels have not been explored, mainly because of the high water table of the region, most of these are dated to the Chaldean dynasty or later. They provide an intimate knowledge of personal dealings by merchants until the Seleucid era. Many were obtained by locals in their illicit diggings and cannot now be associated with their original context. These tablets are mainly contracts and administrative documents. There are, however, a number of literary and religious texts originating in the temples in the post-Achaemenid period up to a.d. 100. A few of these traditional “school-texts” are in Greek on clay tablets. These continued to be copied long after Aramaic had become the official language written on more perishable materials, and they include astronomical observations, diaries, almanacs, and omens.

Later History

A. Fall of Babylon, 539b.c. In 544 Nabonidus returned from Teimā to Babylon, with which he had been in contact throughout his ten-year exile. He does not, however, appear to have taken over control of the city itself again from Belshazzar when, according to the Babylonian Chronicle for his seventeenth year, the gods of the chief cities of Babylonia, except Borsippa, Kutha, and Sippar, were brought into the capital for safekeeping. During Cyrus’ attack on Opis the citizens of Babylon apparently revolted but were suppressed by Nabonidus with some bloodshed. He himself fled when Sippar fell on the 15th of Tešrītu, and the next day Ugbaru, the governor of Gutium, and the Persian army entered the city without a battle. This appears to have been effected by the strategem of diverting the river Euphrates, thus drying up the moat defenses and enabling the enemy to enter the city by marching up the dried-up river bed. This may also imply some collaboration with sympathizers inside the walls. That night Belshazzar was killed (Dnl. 5:30). For the remainder of the month Persian troops occupied Esagila, though without bearing arms or interrupting the religious ceremonies.

On the 3rd of Araḫ-samnu (Oct 29, 539 b.c.), sixteen days after the capitulation, Cyrus himself entered the city amid much public acclaim, ending the Chaldean dynasty as predicted by the Hebrew prophets (Isa. 13:21; Jer. 50f). Cyrus treated the city with great respect, returning to their own shrines the statues of the deities brought in from other cities. The Jews were sent home with compensatory assistance. He appointed new governors, so ensuring peace and stable conditions essential to the proper maintenance of the religious centers.

B. Achaemenid City In Nisānu 538, Cambyses II son of Cyrus II “took the hands of Bēl,” but left the city under the control of a governor, who kept the peace until Cambyses’ death in 522 b.c. There followed the first of the recurrent revolts. Nidintu-Bēl seized power, taking the emotive throne-name Nebuchadrezzar III (Oct.–Dec. 522).Darius, the legitimate king (520–485), put down a further rebellion in the following year but spared the city, building there an arsenal, a Persian-style columned hall (appa danna), as an addition to the palace he used during his stay in the city.

Xerxes, possibly the Ahasuerus of Ezr. 4:6, maintained Babylon’s importance as an administrative center and provincial capital, but the town declined after an uprising that he successfully suppressed. Another rebellion in his fourth year (482) led him to destroy the ziggurat and to remove the statue of Marduk. The walls remained standing in good enough repair for Herodotus, who probably visited the city ca 460 b.c., to describe them in detail (i.178–188), vindicated to a large measure by subsequent researches. There is no evidence that the decree of Xerxes imposing the worship of Ahuramazda was ever taken seriously.

Economic texts from the Egibi family and the Murašu archives from Nippur (460–400 [5 highlights]b.c.) show continued activity despite increasing inflation which more than doubled the rent on a small house, from 15 shekels per annum under Cyrus II to almost 40 shekels in the reign of Artaxerxes I (Longimanus, 465–424), when Ezra and Nehemiah left Babylon to return to Jerusalem (Ezr. 7:1; Neh. 2:1). Artaxerxes II (404–359), according to Berossus, was the first Persian ruler to introduce the statue of Aphrodite or Anahita into the city. Artaxerxes III (Ochus, 358–338) could be the builder or restorer of the appa danna found by Koldewey.

C. Hellenistic Period After his victory at Gaugamela near Arbela (Erbil), Oct. 1, 331 b.c., Alexander marched to Babylon, where the Macedonian was triumphantly acclaimed, the Persian garrison offering no opposition. He offered sacrifices to Marduk, ordered the rebuilding of temples that Xerxes allegedly had destroyed, and then a month later moved on to Susa. He later returned to further his elaborate plans for the sacred city, on which he paid out 600,000 days’ wages for clearing the rubble from the precincts of Esagila (Strabo xvi.1). This debris was dumped on that part of the ruins now called Ḥomera. The Jews who had fought in his army refused to take any part in the restoration of the temple of Bēl (Josephus CAp i.192). Alexander also planned a new port, but this too was thwarted by his death, June 13, 323. The Greek theater inside the east wall (Ḥomera), cleared by Koldewey and Lenzen, may have been built at this time, though it was unquestionably restored in the time of Antiochus IV.

D. Seleucid-Parthians A king list from Babylon written soon after 175 b.c. names the successors of Alexander who ruled the city — Philip Arrhidaeus, Antigonus, Alexander IV, and Seleucus I (323–250). Before Seleucus died Babylon’s economic but not its religious importance had declined sharply, a process hastened by the foundation of a new capital at Seleucia (Tell `Umar) on the Tigris by his successor Antiochus I, in 274 b.c.

E. Later City Babylon’s attraction as a “holy city” continued. The satrap Hyspaosines of Characene suppressed a revolt led by a certain Hymerus in 127 b.c. when the priests of Esagila were active. Hymerus issued coins as “king of Babylon” in 124/23, but by the following year Mithradates II had regained control. An independent ruler Gotarzes I was recognized as ruler in 91–80, and the city lay in Parthian hands (Mithradates III, 58–55) until taken over by a rebel Orodes. It remained a center of Hellenism, despite the opposition of a significant traditional Babylonian priestly party and of a minority of Jews, from among whom may have come Hillel. Babylon supported the Jews in Palestine who opposed Herod (Josephus Ant. xv.2.1–3). The close association between these Jews in Babylon, who enjoyed self-government there in the 1st cent, and their fellows in Jerusalem is suggested in Acts 2:9–11. Dated cuneiform texts up to a.d. 110 show that the site was still occupied. While Babylon may have been the site of an early Christian church (1 Pet. 5:13), there is no evidence (see Babylon in the NT). When Trajan entered the city in 115 he sacrificed to Alexander’s manes but made no reference to the continued existence of other religious practices or buildings. According to Septimius Severus the site was deserted by a.d. 200.

Exploration and Excavation

Since the ancient city of Babylon long lay deserted and unidentified, many early travelers, including Schiltberger (ca 1400), di Conti (1428–1453), Rauwolf (1574), and John Eldred (1583), thought it lay elsewhere, probably at the upstanding remains of ‘Aqar Qūf, W of Baghdad, which resembled the Tower of Babel. Benjamin of Tudela (12th cent), however, considered that the ruins of Birs Nimrûd covered ancient Babylon.

Pietro della Valle, visiting Bâbil in 1616, correctly equated it with Babylon, as did Emmanuel Ballyet in 1755 and Carsten Niebuhr some ten years later. Surface exploration was undertaken by C. J. Rich (1811/12, [6 highlights]1821) and J. S. Buckingham and Mellino (1827). Ker Porter mapped the ruins (1818), as did Coste and Flandin (1841), while soundings were made by R. Mignan (1828) and more seriously by A. H. Layard (1850).

The first systematic excavations were directed by a French consul, Fresnel, with Oppert and Thomas in 1852. Their finds were regrettably lost when a boat containing them foundered at Qurna. Work was continued by E. Sachau in 1897/98, but it was left to the Deutsche Orientgesellschaft under Robert Koldewey to plan and carry out scientific excavations throughout the years 1899–1917. Work began with the Procession Way, the temple of Ninmaḫ, and the palaces (1900), the Ninurta temple (1901), the Ishtar gate (1902), the Persian buildings (1906/07), Merkes (1908), and the rest of the Qaṣr (1911/12).

From 1955 to 1968 the Iraqi Department of Antiquities carried out further clearances, especially of the Ishtar gateway, which was partially restored together with the Procession Way and the palaces. The Ninmaḫ temple was reconstructed, and a museum and rest house built on the site, which is also partially covered by the village of Jumjummah. The German Archaeological Institute has continued its interest in the site by excavating the quay wall and the Greek theater.

See also Archeology of Mesopotamia.

Bibliography.—R. Koldewey, Excavations at Babylon (1914); E. Unger, Babylon, die heilige Stadt (1931); “Babylon” in Reallexikon der Assyriologie, II (1932); O. E. Ravn, Herodutus’ Description of Babylon (1932); W. Andrae, Babylon, die versunkene Weltstadt und ihr Ausgräber Robert Koldewey (1952); F. Wetzel, Das Babylon der Spätzeit (1957); A. Parrot, Babylon and the OT (1958); H. J. Klengel, in Forschungen und Berichte, 5 (1962); J. Neusner, History of the Jews in Babylonia: The Parthian Period (1965); H. W. F. Saggs, in AOTS, pp. 39–56.

D. J. Wiseman