The Areopagus is a hill northwest of the Acropolis in Athens, Greece.

There are two traditions as to how the hill got its name. According to one, it was named for Ares the god of War, who was put on trial there for the slaying of Halirrhotios the son of Poseidon; hence the AV designation in Acts 17:22 (Ares has been identified with the Roman god Mars). The other tradition understands the name Areopagus to mean the “hill of the Arai.” The Arai (“curses”), more popularly known as the Furies, were goddesses whose task was avenging murder. If this tradition is true the name was very fitting, for the Areopagus was the place where cases of homicide were tried. Moreover, at the foot of this hill there is a cave wherein the shrine of these goddesses was located. The goddesses are also known by the names Semnai and Erinyes. Pausanias of Sparta tells of a tradition that the first trial on the Areopagus was that of Orestes, whom the goddesses cursed and pursued relentlessly for the murder of his own mother, Clytemnestra.

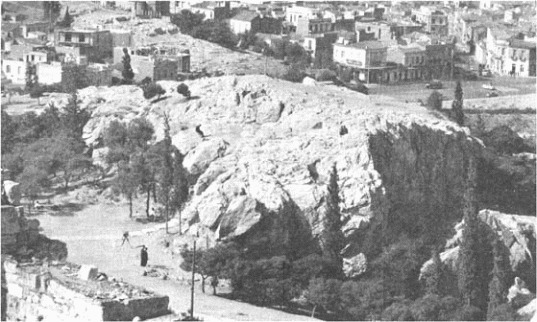

A staircase hewn out of the rock leads to the summit of this hill (which is about 370 ft [113 m] high), where traces of benches are visible forming three sides of a square, also cut out of the stone. At one time, two white stones were also there, upon which the defendant and his accuser stood. They were named “The Stone of Shamelessness” and “The Stone of Pride,” respectively.

The name of the hill was given later to the council whose meetings were held upon it. The council of the Areopagus retained this name even when its meetings were transferred from the hill to the Royal Stoa, which should, perhaps, be identified with the stoa of Zeus Eleutheros in the agora. It is suggested that the council met at times on the Acropolis as well. The council of the Areopagus was similar to a council of elders, and was subject to the king of Athens. It was very influential in the formation of the aristocracy. Aristotle (Pol. viii.2) describes the scope of its power as including the appointment to all offices, the work of administration, and the right to punish all cases. Through the reforms of Solon (594 b.c.) the authority of the Areopagus was greatly limited, though the council did maintain jurisdiction in cases of conspiracy against the state. During the time of Pericles its functions were mainly those of a criminal court. Further transfers of its functions to the Boule, the Ecclesia, and the Popular Court of Law detracted from the prestige of the court, though it retained jurisdiction in cases of homicide. Under Demosthenes it recaptured some of its power and was able to annul the election of certain officers. In times of Roman domination the council of the Areopagus concerned itself with cases of forgery, maintaining correct standards of measure, supervision of buildings, and matters of religion and education. The Areopagus was the court where Socrates met his accusers.

The apostle Paul was brought to the Areopagus by certain Epicureans and Stoics who wished to hear more of his teaching about Jesus and the Resurrection. Since the name Areopagus may be applied to the hill or to the council, there is an ambiguity which has given rise to debate as to whether Paul spoke publicly on the hill or was examined for his religious teaching before the council. Ramsay (SPT) rejected the view that they took Paul to the summit of the Areopagus in an effort to find a more suitable place for him to address the crowd. He considers that pride would have prevented the Athenians from asking Paul, a despised person, to address them in such an honored locality. Furthermore, he asserts that the language of the text will not allow it, for one cannot stand “in the midst of the hill.” It is likely that Paul was examined by the council on account of the religious tenets he was proclaiming. The control the council exercised over public instruction is illustrated by Plutarch’s statement with respect to Cratippus the peripatetic, that Cicero “got the court of Areopagus, by public decree, to request his stay at Athens, for the instruction of their youth, and the honor of their city” (Plutarch Cicero 24.5). Although it is recognized that the council met in various places, its common practice to convene on the hill from which it took its name makes plausible the position of Wright and certain others who consider that Paul stood before the council on the hill of the Areopagus.

Bibliography.—SPT; WBA; F. F. Bruce, Book of the Acts (NIC, 1954); W. A. McDonald, BA, 4 (1941), 1–10; O. Broneer, BA, 21 (1958), 2–28.

D. H. Madvig

From International Standard Bible Encyclopedia