From International Standard Bible Encyclopedia

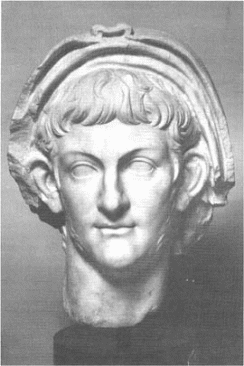

Nero nēʹrō [Gk Nerōn]. The fifth Roman emperor, who was born at Antium in a.d. 37, began to reign October, 54, and died June 9, 68.

I. Parentage and Early Training

Nero’s father was Cnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus (“brazen beard”), a man from an illustrious family but of vicious life. His mother Agrippina, daughter of Germanicus and the older Agrippina, was a sister of the emperor Caligula. Through her mother she was the great-granddaughter of the emperor Augustus, and this gave her son a strong claim to the throne.

Agrippina schemed to make Nero’s imperial claim a reality. He was betrothed and later married to Octavia, daughter of Claudius, who succeeded his nephew Caligula as emperor. After the murder of Claudius’s wife, Agrippina (by then widowed) wed Claudius, the law having been changed to allow her marriage to her father’s brother. She persuaded Claudius to adopt Nero as his son, and the young man, formerly Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, became Nero Claudius Caesar Germanicus. Claudius agreed to make a will in favor of Nero, but when he began to regret disinheriting his own son Britannicus, Agrippina poisoned Claudius. Immediately Nero was proclaimed emperor by the praetorian prefect Burrus; the praetorian guard had been richly bribed. The senate weakly acknowledged the new emperor.

- Reign

A. “Quinquennium Neronis”The first five years (quinquennium) of Nero’s reign were characterized by good government at home and in the provinces and by the emperor’s popularity with the senate and people. Agrippina’s influence over her son was lessened through the efforts of Burrus and Seneca the philosopher, who was Nero’s tutor. One of her efforts to retain her power — a threat to present Britannicus as the rightful heir to the throne — resulted in Nero’s having Britannicus poisoned and eventually banishing Agrippina from the palace. Seneca and Burrus brought about financial, social, and legislative reforms but allowed Nero to indulge in low pleasures and excesses and to surround himself with dissolute companions — habits that the emperor never abandoned.

B. Poppaea Sabina and TigellinusThe wife of Otho, one of Nero’s notorious companions, was Poppaea Sabina, a woman as ambitious as she was unprincipled. She was endowed, according to Tacitus, with every gift of nature except an “honorable mind.” Beginning in 58 she used her husband as a tool to become Nero’s consort. Under her influence Nero shook off all restraints, turned a deaf ear to his best advisers, and plunged deeper into immorality and crime. She allowed, if not persuaded, Nero to give Otho a commission in a distant province (Lusitania). With Nero’s connivance she plotted Agrippina’s death. Agrippina was induced to board a boat that had been carefully constructed to sink, but she saved herself by swimming ashore. She was subsequently killed on a pretext, however, and Nero claimed that she had committed suicide (Suetonius xxxiv; TacitusAnn cxli-cxlviii).

Having openly become Nero’s mistress, Poppaea continued to eliminate her rivals. When Burrus died in a.d. 62, she forced Seneca to withdraw from the court. She had Nero divorce Octavia because of her barrenness and then banish her to the island of Pandateria on a false charge of adultery. Octavia was executed in 62 and her head brought to Poppaea. In 65 Poppaea herself died during pregnancy when Nero in a fit of rage cruelly kicked her.

After his extravagance had exhausted the well-filled treasury left by Claudius, Nero began to confiscate the estates of rich nobles against whom the new praetorian prefect Tigellinus could contrive the slightest charge. Even this tactic did not prevent a financial crisis — the beginning of the bankruptcy of the Roman empire. Worst of all, the gold and silver coinage was depreciated, and the senate was deprived of the right of copper coinage.

C. Great FireThe situation was immeasurably worsened by the great fire that began July 18, 64, in the Circus Maximus and that, with the aid of a high wind, consumed street after street of poorly built wooden houses. When after six days it had almost died down, another conflagration started in a different part of the city. Of the fourteen city regions, evidently seven were destroyed totally and four partially. Nero hurried back to Rome from Antium and superintended in person the work of the fire brigades, often exposing himself to danger. He took many of the homeless into his own gardens. Despite his efforts, numerous rumors accused him of arson (cf. Suetonius xxviii; TacitusAnn xv.38ff). No serious modern historian, however, charges him with the crime.

D. Persecution of ChristiansSince such public calamities were generally attributed to the wrath of the gods, everything was done to appease the offended deity. Tacitus recounted Nero’s scheme to avert suspicion from himself. “He put forward as guilty [subdidit reos], and afflicted with the most exquisite punishments, those who were hated for their abominations [flagitia] and called ‘Christians’ by the populace. Christus, from whom the name was derived, was punished by the procurator Pontius Pilate in the reign of Tiberius. The noxious form of religion [exitiabilis superstitio], checked for a time, broke out again not only in Judea its original home, but also throughout the city [Rome], where all the abominations meet and find devotees. Therefore first of all those who confessed [i.e., to being Christians] were arrested, and then as a result of their information a large number were implicated [reading coniuncti, not convicti], not so much on the charge of incendiarism as for hatred of the human race. They died by methods of mockery; some were covered with the skins of wild beasts and then torn by dogs, some were crucified, some were burned as torches to light at night … . Whence [after scenes of extreme cruelty] commiseration was stirred for them, although guilty of deserving the worse penalties, for men felt that their destruction was not on account of the public welfare but to gratify the cruelty of one [Nero]” (Ann. xv. 44).

Such is the earliest account of the first gentile persecution (as well as the first gentile record of the crucifixion of Jesus). Tacitus clearly implied that the Christians were innocent (subdidit reos) and that Nero used them simply as scapegoats. Some regard the conclusion of the paragraph as a contradiction of this — “though guilty and deserving the severest punishment” (adversus sontes et novissima exempla meritos). But Tacitus meant by sontes that the Christians were “guilty” from the point of view of the populace and that from his own standpoint, too, they merited extreme punishment, but not for arson. Fatebantur does not mean that they confessed to incendiarism, but to being Christians; qui fatebantur means that some boldly confessed, but others tried to conceal or perhaps even denied their faith.

E. Conspiracy of PisoThe tyranny of Tigellinus and his confiscations to meet Nero’s expenses caused the nobles deep discontent, which culminated in the famous conspiracy of 64 headed by C. Calpurnius Piso. The plot was betrayed and an inquisition followed in which perished Seneca the philosopher, Lucan the poet, Lucan’s mother, and later Annaeus Mela the brother of Seneca and father of Lucan (TacitusAnn xvi.21f).

F. Visit to GreeceHaving taken care of every suspected person, Nero abandoned the government in Rome to a freedman, Helius, and made a long visit to Greece (a.d. 66–68). There he took part in muscial contests and games; he won prizes from the obsequious Greeks, in return for which he bestowed on them the “freedom” of their province.

G. DeathIn 66 began the revolt in Judea that would end in the destruction of Jerusalem, and in 68 the revolt of Vindex, governor of Lugdunum (Lyons) in Gaul, was put down. Shortly afterward came the fatal rebellion of Galba, governor of Hither Spain, who declared himself legatus of the senate and Roman people. Helius persuaded Nero to return to Rome. The emperor confiscated Galba’s property and could have crushed him, but the doubts, fears, and distractions that overwhelmed him greatly helped Galba’s cause. Nero lost the support of the praetorian guard that made him emperor. He committed suicide, bringing to an end the line of Julius Caesar.

- “Nero Redivivus”

A freedman, two old nurses, and his cast-off concubine Acte cared affectionately for Nero’s remains, and for a long time flowers were strewn on his grave (Suetonius lvii). Soon the strange belief arose that Nero had not really died but was living somewhere in retirement, perhaps in Parthia, and would return shortly to bring great calamity upon his enemies or the world (Suetonius lviii).

Some Jews amalgamated this belief with their concept of the antichrist. AscIsa 4 (1st cent a.d.) clearly identifies the antichrist with Nero; the idea repeatedly occurs in both Jewish and Christian sections of the Sibylline Oracles (3:66ff; 4:117f; 5:100f, 136f, 216f).

How far the Christians regarded Nero as the historical personage of the antichrist is disputed. It would be natural if they had been inflenced by contemporary thought about the revival of Nero. W. Bousset (Die Offenbarung Johannis [1906], inloc) regarded the beast of Rev. 13 as Rome and the smitten head “whose mortal wound was healed” as Nero; some scholars think that Rev. 17:10f refers to Nero. Such passages in Revelation may refer to the spirit of Nero but certainly not to Nero himself. Some scholars have applied the number 666 in 13:8 to Nero, but it suits many other wicked rulers as well (cf. Farrar, ch 28, 5). (See Number VI.)

- Nero and Christianity

A. Nero and the New Testament Although the name Nero does not occur in the NT, he must have been the Caesar to whom Paul appealed (Acts 25:11) and at whose tribunal Paul was tried after his first imprisonment. Nero probably heard Paul’s case in person, for he showed much interest in provincial cases. It was during the earlier “golden quinquennium” of Nero’s reign that Paul addressed his Epistle to the Christians at Rome. Some have argued that Paul was probably martyred near Rome in the last year of Nero’s reign (a.d. 68), but it is much more probable that Paul died in the first Neronian persecution of 64.

The NT never states that Peter visited Rome. The belief in such a visit arose later from tradition (cf. Clement of Rome, Ignatius, Papias, and later Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria, and the Liber Pontificalis [catalog of popes]). Although there is no reliable evidence that Peter was bishop of Rome, and while it is certain that if he went to Rome it was for brief period, it is highly probable that he visited the city in old age and was martyred there under Nero.

B. Neronian Policy and ChristianityBefore Nero, the Roman government had been on friendly terms with Christianity, for it was not prominent enough to disturb society greatly and was probably confused with Judaism, a licensed religion (Tertullian Apol 21). Paul urged the Christians of the capital to “be subject to the governing authorities” as “instituted by God” (Rom. 13:1f). His high estimation of the Roman government as a power operating for the good of society was probably enhanced by his own experiences before his final imprisonment. By that time the difference between Christianity and Judaism had become apparent to the Roman authorities, perhaps because of the growing hostility of the Jews, or perhaps because of the alarming progress of Christianity, and policy had begun to change for the worse.

According to one view, the Neronian persecution was a unique attempt to satisfy the revenge of the mob and was confined to Rome. Christians were put forward as arsonists to remove suspicion from Nero. They were persecuted on account of false charges of Thyestean feasts, Oedipal incest, and nightly orgies; their withdrawal from pagan society and their exclusive manners caused the charge of “hatred of the human race.” The evidence of Tacitus seems to support this view.

The preferable view, however, represented by Ramsay (CRE, ch 11) and E. G. Hardy (Studies in Roman History, ch 4), is that Christianity was permanently proscribed as a result of Nero’s persecutions. In this view, the accounts of Tacitus and Suetonius are reconcilable; Tacitus gave the initial step, and Suetonius’s inclusion of the persecution of Christians in a list of seemingly permanent police regulations (Nero xvi) indicates the outcome — an established policy of persecution. Ramsay maintained that Christians had to be tried and their crimes proved before they were executed, but Hardy argued that henceforth the Name itself was proscribed.

There is no reason to suppose that the Neronian persecution of 64 extended throughout the empire. The authorities for a general Neronian persecution and formal Neronian laws against Christianity are late. But the emperor’s example in Rome would have greatly influenced the provinces; the persecutions established a precedent of great importance in the imperial policy toward Christianity.

Bibliography.—CAH, X, ch 21; L. H. Canfield, Early Persecutions of the Christians (1913); CRE; Eusebius HE ii.25; F. W. Farrar, Early Days of Christianity (1882); E.R. Goodenough, Church in the Roman Empire (1931), ch 12; H. M. Gwatkin, Early Church History, I (1909); E. G. Hardy, Christianity and the Roman Government (1925); B. W. Henderson, Life and Principate of the Emperor Nero (1903).

S. Angus

A. M. Renwick