From International Standard Bible Encyclopedia

Dead Sea Scrolls The name generally given to the manuscripts and fragments of manuscripts discovered in caves near the northwestern end of the Dead Sea in the period between 1946 and 1956. They are also called by several other terms, such as the `Ain Feshka Scrolls, the Scrolls from the Judean Desert, and — probably best of all — the Qumrân Library (QL). The name Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS), however, has become firmly attached in English, and likewise its equivalent in several other languages, in spite of its imprecision. According to many experts, this is one of the greatest recent archeological discoveries, and for biblical studies certainly one of the greatest manuscript discoveries of all times.

I. Discoveries

A. Original Finds

The story of the “discovery” of the DSS has been told many times, and with some significant variations.

As reconstructed by Trever, the first “discovery” was made by three bedouin of the Ta’amireh tribe, Muhammed Ahmed el-Hamed (known as “edh-Dhib”), Jum`a Muhammed Khalib, and Khalil Musa, who by chance came upon what later was to be known as Cave 1 and discovered a number of jars, some containing manuscripts. The date is not known, but it was probably toward the end of 1946 or early 1947. In March 1947 the scrolls were offered to an antiquities dealer in Bethlehem, but he did not buy them. In April, the scrolls were taken to Khalil Eskander Shahin (“Kando”), a shoemaker and antiquities dealer in Bethlehem, who became an intermediary in numerous sales of the materials. Meanwhile George Isha`ya Shamoun, a Syrian Orthodox merchant who often visited Bethlehem, was taken to Cave 1 by bedouin, and later he and Khalil Musa secured four scrolls. Isha`ya had in the meantime (about April 1947) informed St. Mark’s Monastery of the find, and the Metropolitan, Mar Athanasius Yeshue Samuel, offered to buy them.

Four scrolls were taken to the monastery about July 5 by Jum`a Muhammed, Khalil Musa, and George Isha`ya, but they were mistakenly turned away at the gate. About July 19, Kando purchased scrolls from the bedouin and sold them to St. Mark’s Monastery for twenty-four Palestinian pounds ($97.20). That same month, Fr. S. Marmardji of École Biblique was consulted about the scrolls, and he and Fr. J. van der Ploeg went to the monastery to see them. Van der Ploeg recalls with some embarrassment that he mistakenly identified the scrolls as medieval. Other scholars also examined the scrolls, but none recognized their great value.

In addition to the four scrolls that were sold by Kando, three others were sold by Jum`a and Khalil to Faidi Salahi, also an antiquities dealer. He paid seven Palestinian pounds ($28.35) for the scrolls and twenty piasters (about 80 cents) each for two jars. These were the first MSS to come into the possession of recognized scholars, for two of them were purchased by E. L. Sukenik of Hebrew University on Nov. 29 and the third on Dec. 22, 1947. The MSS were later identified as the Hebrew University Isaiah Scroll (&1QISAB;), the Order of Warfare, or the War of the Sons of Light Against the Sons of Darkness, later called the War Scroll (1QM), and the Thanksgiving Hymns (1QH). (For details of the negotiations, see Yadin [Sukenik’s son], Message of the Scrolls.)

Sukenik had heard about the other scrolls in the possession of St. Mark’s Monastery, was permitted to examine them, and offered to buy them. Fr. Butrus Sowmy, librarian of the monastery, contacted the American School of Oriental Research in Jerusalem on Feb. 18, 1948, seeking to get a better idea of the value of the scrolls, and he and his brother Ibrahim took four scrolls to the school on the following day. They were examined by J. Trever, a postdoctoral fellow at the school. Excited by the Hebrew paleography, Trever managed to secure permission to visit the monastery, and then was given permission to photograph the scrolls. On Feb. 21 and 22 and again on March 6–11, he photographed three of the scrolls, column by column, and his photographs became the basis for the editio princeps of these scrolls, later identified as the Isaiah Scroll (1Qisaa), the Habakkuk Commentary (1QpHab), and the Manual of Discipline (1QS). The fourth scroll could not be opened. From a fragment, it was named the “Lamech Scroll,” and later, when opened by J. Biberkraut, an expert in unrolling delicate MSS (cf. BA, 19/1 [1956], 22–24), it was renamed the Genesis Apocryphon (1QapGen).

To understand the confusion that is found in various reports, one must bear in mind that the British Mandate was nearing its end, and sporadic fighting between Arabs and Jews was taking place. On Nov. 29, 1947, the day that Sukenik purchased the first of the scrolls, the United Nations voted to partition Palestine and establish an independent nation of the Jews, and on May 14–15, 1948, the Mandate ended, the State of Israel came into being, and warfare broke out on a large scale. For obvious reasons, Fr. Sowmy took the scrolls in his possession to Beirut for safekeeping (March 25, 1948); he returned to Jerusalem and was later killed in the bombing that damaged St. Mark’s Monastery. Athanasius Samuel took the four scrolls from Beirut to New York in January 1949. Efforts were made by several institutions to purchase the scrolls, but the Metropolitan was asking a huge sum, reportedly a million dollars, for them. In February 1955 the Prime Minister of Israel revealed that Yadin had secretly purchased the scrolls on July 1, 1954, for $250,000, and that the scrolls were in a vault in the Prime Minister’s office. Subsequently they were moved to a building that had been built for them near the University, known as the Shrine of the Book. All the scrolls of the original discoveries in Cave 1 were now in Israel.

It was impossible for qualified scholars to visit and explore the cave where the scrolls allegedly had been found, so there was much distrust of the story told by the bedouin and repeated by many others. There were unauthorized visits to the cave in the summer and again in the fall of 1948, and many additional fragments of scrolls and other items were recovered. It became obvious that some controlled exploration should be undertaken.

In September 1948 the first articles on the scrolls were published, along with photographs, both by the American Schools of Oriental Research and by Hebrew University, and “the Battle of the Scrolls” had begun. For many months there was considerable discussion of the date and authenticity of the discoveries. It is probably correct to state that never in history had so many scholars from so many different nations become involved in the problems associated with a single discovery.

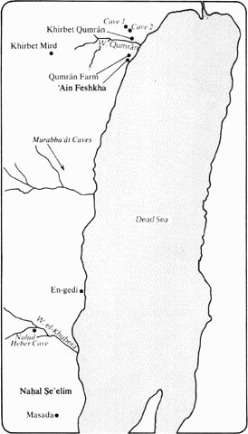

Capt. P. Lippens, a Belgian army officer serving as observer for the United Nations, was able to interest Major General Lash, British commander of the Arab Legion, Colonel Ashton, archeological advisor to the Legion, and G. L. Harding, Director General of the Department of Antiquities of the Hashemite Kingdom of the Jordan. An expedition and a detachment of the Arab Legion under Captain A. ez-Zeben located Cave 1, only to find that it had been almost completely looted. Systematic excavation was undertaken by Harding and Père R. de Vaux, director of École Biblique, between Feb. 8 and March 5, 1949, and thousands of MS fragments, together with jar fragments, pottery remains, and fragments of the cloth that had wrapped the scrolls, were recovered. (For an inventory, cf. Trever, pp. 149f) It seemed certain, although hotly disputed by some, that the cave of the original finds had indeed been discovered, and that the bedouin story was basically correct. The cave was located by Harding at coordinates 1934.1287 of the Palestine Survey Map, which is about 6.8 mi (11 km) S of Jericho, 2.2 mi (3.5 km) N of `Ain Feshkha, in the marly cliffs about 1.2 mi (2 km) from the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea and about 1000 ft (305 m) above the surface of the sea (which is 1292 ft [394 m] below sea level).

B. Subsequent MS Discoveries

Materials that were obviously related to the original finds were turning up in the hands of various antiquities dealers. Caves in Wâdī Murabba‘ât as well as in Khirbet Mird were discovered by bedouin. Meanwhile, expeditions led by École Biblique and the American Schools were exploring the region and finding other caves. Between March 10 and 29, teams explored the region for 5 mi (8 km) N and S of Wâdī Qumrân, discovering 230 caves, of which twenty-six contained pottery similar to that found in Cave 1, but only one (Cave 3) contained MS fragments.

It is important, to assure that scholarly control was maintained, to note that Cave 3 was discovered by an expedition, Cave 4 (which had been discovered by bedouin) was excavated by a scholarly expedition, who also discovered Cave 5, and Caves 7, 8, 9, and 10 were discovered by archeologists working at Khirbet Qumrân. The marked relationship of the discoveries from the various Qumrân caves (with the possible exception of the copper scroll from Cave 3) makes it clear that the materials in all of the caves, whether discovered by bedouin or acheological expeditions, are of common origin. (The caves were numbered in the order in which they were discovered.) On the other hand, the discoveries in the caves in Wâdī Murabba‘ât, Khirbet Mird, and Naḥal Ḥeber belong to different categories, and should not be confused with the Dead Sea Scrolls. Caves 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, and 10 were located in the terrace around Khirbet Qumrân, while Caves 1, 2, 3, 6, and 11 were in the cliff that extends north and south, to the west of the Jordan Valley and the Dead Sea. The most significant cave yields were from Caves 1, 4, and 11, which will be discussed more fully. Cave 3 yielded the “Copper Scroll” (3QInv or 3Q15); Cave 6 provided a quantity of papyrus fragments and significant fragments of the “Damascus Document” (6QD CD is exemplar from Cairo); Caves 2, 5, and 7 through 10 yielded smaller quantities of MS fragments.

The most extensive MSS were found in Cave 1 (mentioned above) and Cave 11, which yielded at least seven MSS, including a Targum of Job (11QtgJob), a portion of Leviticus in Paleo-Hebrew script (11QpaleoLev), a scroll of Ezekiel (11QEzek) in bad condition, and three partial scrolls of Psalms (QPsabc11). The large Psalms scroll (QPsa11) contains thirty-six canonical Psalms, the Hebrew text of Ps. 151 (previously known only from Greek, Syriac, and Old Latin texts), and eight Psalms not otherwise known. It is possible that the “Temple Scroll” (seized by Israelis in 1967 from a Jerusalem antiquities dealer, provisionally identified as 11QTemple) also came from Cave 11.

In addition to the more extensive MSS or portions of MSS, great quantities of fragments of MSS were recovered, the importance of which is at least equal to that of the MSS that suffered lesser damage. From Cave 1 came fragments that were at first thought to be part of the Manual of Discipline (1QS), namely the Order of the Congregation (QSa1 or 1Q28a) and the Benedictions (QSa1 or 1Q28b). There were also fragments of commentaries on Micah, Ps. 37, and Ps. 68, as well as fragments of the Book of Mysteries (1QMyst or 1Q27), the Sayings of Moses (1QDM or 1Q22), and a portion of Daniel including 2:4, where the language changes from Hebrew to Aramaic (QDana1). Cave 4 yielded about 40,000 fragments, representing about 382 different MSS, of which more than 100 are biblical. An international team of eight scholars worked for several years putting together the pieces of this gigantic jigsaw puzzle, and the result included portions of every book of the Hebrew Bible except Esther, fragments of apocryphal works not previously known in Hebrew, and many extrabiblical works, most of which had not previously been known. Among the more significant discoveries are: a Florilegium or collection of mesianic promises (4QFlor); a portion of Gen. 49 with commentary, known as the Patriarchal Blessings (4QBless); a document that sheds some light on the messianic beliefs of the Community, known as the Testimonia (4QTestim); a commentary on Ps. 37 (4QpPs37); fragments of seven MSS of the Damascus Document (4QDa-g); fragments of the War Scroll (4QM); and portions of Daniel where the language changes from Aramaic to Hebrew (Dnl. 7:28–8:1, 4QDana,b).

A full inventory of the published materials from these caves can be found in J. A. Fitzmyer, The Dead Sea Scrolls: Major Publications and Tools for Study (1975), pp. 11–39. Fitzmyer also lists the published discoveries from Masada, Wâdī Murabba‘ā̂t, Naḥal Ḥeber (Wâdī Ḫabra), Naḥal Ṣe’elim (Wâdī Seiyal), Naḥal Mishmar (Wâdī Mahras), Khirbet Mird, and pertinent texts from the Cairo Genizah (pp. 40–53), as well as lists that contain some of the unpublished materials (p. 65). There is no published inventory of all the items discovered at Qumrân.

C. The “Monastery” ofQumrân

The region above the cliffs that flank the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea is a shallow depression known as el-Buqei`a. It is cut by a seasonal river or wadi that bears several names, but where it cuts down through the cliff it is best known as Wâdī Qumrân. At the base of the cliff is a plateau or terrace formed by the detritus from the cliff, presumably when it was eroded by an unusual amount of water during the last Pluvial Age. Wâdī Qumrân has since cut its way through this plateau that rises about 330 ft (100 m) above the surrounding littoral. The cliff is cut by a number of similar wadis, of which three others might be mentioned S of Wâdī Qumrân is Wâdī Nâr, which issues from the confluence of the Kidron and Hinnom Valleys SE of Jerusalem. S of Wâdī Nâr is Wâdī Murabba‘ât. Considerably further S are En-gedi, Naḥal Ḥeber, Naḥal Ṣe’elim, and Masada. About 6 mi (10 km) W of Qumrân on Wâdī Nâr is Khirbet Mird. Our present interest, however, focuses on the ruins located on the plateau at Wâdī Qumrân, known by the Arabic name Khirbet Qumrân (“the ruins of Qumrân”).

The ruins had long been known, but never excavated. In 1873 the French orientalist Canon Clermont-Ganneau noted and described a ruin near Qumrân. A. Vincent had visited the ruins in 1906 and G. Dalman in 1914. Dalman had identified the site — not incorrectly — as a Roman fort. When the official examination of Cave I was being conducted (1949) the ruins were explored, but it was concluded that there was no relationship between the ruins and the Scrolls’ cave. But when more discoveries were made in the vicinity it was decided to make a thorough archeological excavation of the ruins. This was conducted in five campaigns from 1951 to 1955. Excavations were also made in the area between Wâdī Qumrân and `Ain Feshkha in a sixth campaign during 1958. Harding and de Vaux were in charge of the excavations. (The definitive account is given by de Vaux in Archaeology.)

The first season (1951) yielded coins and pottery that appeared to link the buildings to the same period that was indicated by the jars from the caves and by the paleography of the scrolls, namely Early Roman. After the exciting discoveries of 1952 that included five Qumrân caves and four Murabba‘ât caves, the archeologists returned to Khirbet Qumrân with a new zeal. The second and third seasons revealed the nature of the community that had occupied the ruins, and, in the light of the Manual of Discipline (1QS), linked it definitely with the community of the scrolls.

The archeologist, of course, must work from the top downward, whereas his reconstruction of the history must be just the reverse. On the surface of the terrace a complex of buildings and a water system cover an area of approximately 345 ft (105 m) N-S and 250 ft (76 m) E-W. The walls are built on a grid that runs NNE-SSW. The principal distinguishing points for identifying corresponding areas of the different levels are: (1) a circular cistern about 20 ft (6 m) in diameter toward the western side of the complex; (2) the noticeably heavier walls and height of a tower about 39 by 42 ft (12 by 13 m) in the north-central part of the complex; and (3) a rectangular complex about 114 by 98 ft (35 by 30 m) joined to the tower, with the tower at its northwestern corner.

The earliest construction, identified by pottery sherds of Israelite style (including a jar handle bearing a stamp reading lmlk and some ostraca), comprised the circular cistern and the rectangular complex. This was identified by de Vaux as probably not earlier than the 8th cent b.c., on the basis of the pottery and the writing on the ostraca. The site has often been identified as ‘Îr-hammelaḥ (“City of Salt”; Josh. 15:62). At any rate, it has no connection with the DSS, for it suffered violent destruction centuries earlier.

Level IA, on the other hand, was clearly the work of new inhabitants. At this time the southern wall of the rectangular area was extended, a north-south wall was joined to it (bringing the circular cistern into this building complex), and a number of small rooms were added N of the round cistern and W of the tower. Two rectangular cisterns, an aqueduct, and a common settling basin were dug, one N and one E of the round cistern. A potter’s shop was added at the southeastern corner of the compound. Coins found in this level suggested that it was occupied during the time of Alexander Janneus (103–76 b.c.), and was possibly constructed in the days of John Hyrcanus (135–104 b.c.) or one of his predecessors.

The complex came much closer to completion in Period IB (Level IB). Workshops and storerooms were added W of the circular cistern. A large hall — the largest in the entire compound (72 by 15 ft [22 by 4.5 m]) — with a smaller adjoining room, was added S of the main building complex, workshops were built at the southeastern part of the area, and a complicated water system was installed.

An aqueduct brought the water from Wâdī Qumrân, where it cut through the cliffs, to the northwestern corner of the community area. Here it encountered piles of stones, which broke the current, and entered a large settling basin, near which was a bath. From the basin a channel led to the round cistern and the newer rectangular cisterns. Thence a channel led to another settling basin, which fed a very large rectangular cistern, 39 by 16 ft (12 by 5 m) SW of the main complex, and a second large rectangular cistern, 59 by 10 ft (18 by 3 m), which was dug between the main building and the new large hall. A branch channel led to a small, square basin, and from there the channel branched to feed a cistern E of the main building and another complex of cisterns at the south-eastern part of the area, the largest of which was 56 by 23 ft (17 by 7 m). Some of these cisterns and basins seem clearly to have been associated with the potter’s shop and other workshops in that area. The large- and medium-size cisterns had steps leading down into them. All were plastered with clay that is impervious to water. When some of the clay was removed, it was apparent that the cisterns had been lined with masonry and then plastered over. Altogether there were seven (possibly eight) cisterns, six decantation or settling basins, two smaller cisterns described as baths, and a tank for tempering potter’s clay. There is only one round cistern, which is also the deepest of all the cisterns, and while it comes from the Israelite period (Iron II), it had been thoroughly cleaned by the later occupants, for no Israelite remains were found in it. The entire water system strongly suggests that this was not a complex of individual residences but a commune of some sort. The number of cisterns that cannot be explained as serving for water storage or for industrial purposes, specifically those with steps leading down into them and particularly those where the steps are divided to suggest one-way traffic, suggest that some kind of ritual bathing was a practice of the community.

The one large hall, S of the main building and separated from it by a large cistern with divided stairway, and the smaller room that adjoins the hall lend support to this tentative conclusion. The smaller room, 23 by 26 ft (7 by 8 m) contained 210 plates, 708 bowls in piles of twelve, 75 drinking vessels, 38 pots, 11 pitchers, and 21 small jars. The contents identified the room as a pantry, and the adjacent structure as a combination assembly hall and dining room.

The area W of the main building contained what appeared to be workshops and storage rooms, and at its southern end what de Vaux described as possibly a stable for beasts of burden. The area E of the main building contained also workshops and a pottery industry, described by de Vaux as “the most complete and best preserved in Palestine” (RB, 61 [1954], 567).

Between the western shop area and the large settling basin were found a number of containers with bones of animals which obviously had been butchered and boiled or roasted. Upon examination they proved to be from sheep, goats, and bovines. It is not clear, however, why the bones were carefully preserved. A likely suggestion is that the bones were the remains of sacred meals and were considered to be too holy to be simply thrown away.

Coins recovered from level IB included three of the time of Antiochus VII that could be precisely dated, 132/131, 131/130, and 130/129 b.c., and altogether eleven Seleucid coins. After the Seleucid era Jewish coinage was used, including 143 coins of Alexander Janneus (103–76 b.c.), one of Salome Alexandria and Hyrcanus II (76–67 b.c.), five of Hyrcanus II (67 and 63–40 b.c.), four of Antigonus Mattathias (40–37 b.c.), and one of the third year of Herod the Great (35 b.c.).

A severe earthquake left its evidence in a cleft that runs the full length of the compound, just E of the eastern wall of the main building, dropping the eastern side of the cleft 20 in (50 cm.) lower than the rest of the complex. The cisterns E of the main building were destroyed and later abandoned. Evidence of fire is also found. The date of this earthquake can be established from the writings of Josephus, for he records that it occurred in the seventh year of Herod, at the time of the battle between Octavius Caesar and Antony at Actium, i.e., in the spring of a.d. 31 (Ant xv.5.2 § 121; BJ i.19.3 § 370).

Level II clearly indicated occupation by much the same group as Level I. The buildings had been cleaned, with the result that evidence of Period IB was removed. This debris had been placed in a dump N of the complex, and a trench made by the archeologists recovered a quantity of remains, including coins, from Period IB. Repairs were made where earthquake damage occurred. The cisterns E of the main building were abandoned and the water channel blocked. The most important alteration was the covering over of a court alongside the rooms by the western wall of the main building, and reconstruction of a second floor area above it. When this subsequently collapsed (at the time of the destruction that ended Period II, no doubt), the debris found by the excavators gave evidence of much importance. A number of pieces of burned brick covered with plaster were recovered, which, when reconstructed in the museum, formed a long, low table, 16.4 by 1.3 ft (5 m by 40 cm.), and 19.6 in (50 cm.) high, along with fragments of a bench. Also found in the debris were two inkwells, one bronze and one pottery, from the Early Roman period. The upper room was identified as a “scriptorium,” were the manuscripts of the community were produced.

East of the tower was the kitchen area with five fireplaces, basins, and other items. A mill for grinding grain was found in another area, and there was a well-designed area for latrines.

Pottery remains, coins, etc., from Period II were plentiful, suggesting that the end had come suddenly. This was confirmed by the widespread destruction to the buildings, and a layer of ash that contained iron arrowheads. All evidence suggests a military action. The testimony of the coins, eighty-three of which were year 2 of the First Revolt, and five of year 3 — the latest coins of Level II — dates the destruction a.d. 68/69. An early report that a coin or coins surcharged wih “X” of the Roman Tenth Legion had been found has been retracted by de Vaux (Archeology, p. 40, n 1). The account in Josephus is not easy to follow, but it seems certain that the Tenth Legion, or a detachment of it under Trajan, was garrisoned at Jericho and from there moved on Jerusalem (BJ v.1.6 § 42). We may assume that part of this legion moved through Qumrân and on to Jerusalem via Wâdī Nâr or another route, devastating the Qumrân community on the way.

Level III adds little to this study. Evidence indicates that it was occupied for a brief period as a Roman outpost and then again, probably by Jewish rebels, at the time of the Second Revolt. The complex of buildings was not restored to the usage of Periods I and II.

East of the buildings, and separated from the complex by more than 165 ft (50 m), was a cemetery with more than 1100 graves, arranged neatly in rows and sections, the bodies placed on their backs, lying N-S with the head to the south, and the arms crossed over the pelvis or placed alongside the bodies. At the eastern edge of the terrace was another group of graves, less regular. Among the six bodies that were examined here were four women and a child.

The excavations of the region betwen the ruins and ’Ain Feshkha, 2 mi (3 km) S, indicated that this was also used by the same community. Farm buildings, stables, tool sheds, an irrigation system, and rooms that gave evidence of being used for tanning leather were identified. The water that flows abundantly from the springs at ’Ain Feshkha is drunk by animals, but it appears to be too brackish for the cultivation of cereals, although it is suitable for date palms. We may assume that the community grew the barley or wheat that it used in el-Buqei‘a above the edge of the cliffs.

From the number of graves, the number of dishes and bowls in the pantry, and the period of time that Levels I and II were occupied, the size of the community at any given time can be estimated at about two hundred persons. The presence of skeletons of females and a child and the provision for admission of women and children to the community suggest that this was not strictly a monastery, but the rigors of life there and the fact that all of the exhumed skeletons in the main part of the cemetery were males suggest that most of the members were men.

The relevance of the excavation of Khirbet Qumrân to the dating and interpretation of the DSS will become apparent upon examination of the Scrolls in detail.

II. The Qumrân Community

A. Manuscript Evidence

From the caves at Qumrân came the remains of hundreds of MSS that could be categorized as follows: canonical scriptures, i.e., copies of the books of the Hebrew Bible (with the exception of Esther); deuterocanonical scriptures, i.e., those in the Apocrypha; extracanonical scriptures, sometimes classified as pseudepigraphical; and sectarian documents, i.e., those which appear to be the product of the community and which relate specifically to its life and beliefs. Since some of the works not previously known seem to be more in the category of apocryphal or pseudepigraphical writings, the lines are not too firmly drawn, but that should present no serious problems for this study, which will deal principally with the sectarian literature.

The MSS that pertain uniquely to the sect are: the Manual of Discipline (1QS), the Damascus Document (CD), the Thanksgiving Hymns or Hôdāyôt (1QH), the War Scroll (&1QM;), the Order of the Congregation (QSa1 or 1Q28a), the Benedictions (QSa1 or 1Q28b), the pešārîm or comms on portions of Scripture such as the Habakkuk Commentary (1QpHab), and several other more fragmentary works. The Temple Scroll (11QTemple), not yet published at this writing, also should be included. Possibly its choice of extracanonical documents would tell something of the sect, but that approach is rather subjective. See Plate 16.

The introduction of the Damascus Document into this list must be justified. As soon as the Manual of Discipline (1QS) was published, scholars began to point out its similarity to what was known as the Zadokite Fragments or the Damascus Document. A quantity of MSS had been discovered in the Genizah of the Ezra Synagogue in Old Cairo in 1897 and taken to the library of Cambridge University. S. Schechter, president of Jewish Theological Seminary, New York, identified a number of fragments as similar in character and content, and published them (Fragments of a Zadokite Work [1910]). The work drew the attention of many scholars, and the bibliography from 1910 to 1946 (the year before the DSS came to the attention of scholars) is voluminous (see L. Rost, Die Damaskusschrift [1933]; H. H. Rowley, Zadokite Fragments and the Dead Sea Scrolls [1952]). Since the provenance of these fragments was Cairo, the siglum CD (for Cairo, Damascus) was assigned to the work. In spite of striking parallels between 1QS and CD, many scholars resisted the conclusion that CD was a product of the Qumrân community, until fragments of the Damascus Document were recovered from Cave 5 (5QD = CD 9:7–10), Cave 6 (&6QD; = CD 4:19–21; 5:13f; 5:18–6:2; 6:20–7:1; and a fragment not in CD), and fragments of five (or seven?) different MSS from Cave 4 (4QDa-e). The questions of how the document got to Cairo and how two MSS of it came to be produced in the 10th and 11th cents have not yet been satisfactorily answered.

But can the MSS be connected with the buildings at Khirbet Qumrân and ‘Ain Feshkha? This is a crucial question, for unless it is established beyond reasonable doubt that the documents and the building complex belong to the same community, the one cannot be used to interpret the other. (De Vaux has taken this up in detail in Archeology, pp. 91–138.) The evidence may be summarized as follows. The MSS are ancient. From paleographic, linguistic, textual, and physico-chemical studies, they must be dated between the 3rd cent b.c. and the Second Revolt. The MSS were found in the caves in the immediate vicinity of Khirbet Qumrân, in some cases in caves that were in the steep-sloping sides of the plateau on which the buildings were located. The MSS had been deposited in the caves in antiquity, as evidenced by dust and other material that had covered them, and the pottery that was found in the same level in the caves was of the same type as the pottery in the ruins. In some cases (such as Cave 4), there was clear evidence that the caves had been dug and the MSS placed on the fresh ground in great haste, with no signs of previous or later occupation. Further, the evidence of the nature of the Qumrân community as described in the MSS is in agreement with the archeological discoveries of the Khirbet, and the coins, pottery, and carbon-14 testing of material found with the MSS fit precisely the dates established for the MSS by the means mentioned above. No other theory suggested for the MSS has any support other than the ingenuity of the theorizers, and no other explanation of the ruins can be supported by other evidence. The MSS explain the Khirbet, and the ruins explain the presence and contents of the MSS.

B. Origin of the Community

There can be no doubt that the Qumrân community was a Jewish sect, using the term “sect” in much the same way it is used by Josephus and in Acts. The great quantity of Jewish scriptures, and the stress on the Torah in the sectarian documents, make this irrefutable. The community members thought of themselves as a Jewish remnant, living in the “end-time of the ages,” penitents whose God had remembered them and raised up for them a “teacher of righteousness” (or a “righteous teacher” — the annexion of the words [construct] can indicate either an objective genitive [what the teacher teaches] or a descriptive genitive [the character of the teacher]). If the figures in CD 1:3–13 are pressed literally, God’s “visitation” occurred 390 years after the fall of Jerusalem to Nebuchadrezzar, which could be 208/207 b.c. (from 597 b.c.) or 197/196 (from 586 b.c.), and twenty years later God raised up the teacher of righteousness (i.e., 189/188 or 178/177 b.c.). It should be noted that nowhere is the teacher presented as the founder of the sect. It should also be noted that such mathematical and chronological precision should not be demanded.

The dates thus inferred point to a time of crisis in Jerusalem. Antiochus III the Great (223–187 b.c.) had defeated the Egyptian forces at Paneas (Caesarea Philippi) in 198 b.c., and had taken Palestine from the Ptolemies. His son Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175–164 b.c.) plundered Jerusalem, exacted a large tribute from the Jews, and in 167 b.c. erected a pagan altar at the temple where the sacred altar had stood. Meanwhile, there was a strong movement among the Jews to end the separation of Jews and Gentiles, to erase the marks of Judaism, and become Greek. The story is told in great detail in 1 Maccabees. Onias III, high priest 185–174 b.c., was a pious man, but he was deposed by his brother Jason who sought to complete the hellenization of the Jews (2 Macc. 4:7–26). Such was the background of the revolt led by Mattathias of the Hasmonean line, who was joined by the Hasideans (ḥasîḏîm, “faithful/pious ones”). This is not the place to give the details of the period that followed, but simply to note that it is in the time of John Hyrcanus (134–104) that Josephus first mentions the Pharisees and Sadducees. The Pharisees (perûšîyim, “separated ones”) are perhaps the successors of the Hasidim, for when the Hasmoneans (Macabbees) took over the political power, the Hasidim separated themselves from the Hasmoneans. The name “Sadducees” is the source of much discussion. The best etymology seems to be ṣeḏôqîyim or benê ṣāḏôq; in other words, they claimed descent from Zadok (cf. 2 S. 8:17; Ezk. 40:46; 44:15; etc.) to support their claim to the priesthood. (See R. North, CBQ, 17 [1955], 173.) A good case can be made for the division of the Hasidim (or the Pharisees) into several groups, one of which was the Essenes. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the original of which Qumrân was a direct descendant (or one of several descendants) came into existence in the period of the struggle against the hellenizers. Attempts to identify the teacher of righteousness or the “wicked priest” of Qumrân literature with historical persons, however, have not been convincing (discussed more fully in LaSor, “A Preliminary Reconstruction of Judaism in the Time of the Second Temple in the Light of the Published Qumran Materials” [Th.D. diss, University of Southern California, 1956]).

Against this brief historical background, some of the statements in the DSS take on a richer meaning. The Qumrânians were “the Penitents of Israel who go out from the Land of Judah,” to “dwell in the land of Damascus” (CD 6:5f). Whether Damascus is to be understood literally or, as some hold, to be taken as a reference to Qumrân is not clear. The community took the reference to the “sons of Zadok” in Ezk. 44:15 as applying to itself (CD 3:21–4:2). It expressed contempt for the “priests of Jerusalem” (1QpHab 9:4f), particularly for “the wicked priest” who “did works of abominations and defiled the temple of God” (12:7–9). Possibly the same wicked priest is referred to as “the man of the lie” (2:11f) and “the preacher of the lie” (10:9).

C. Names for the Community

The most common term, used more than a hundred times, is “the Community” (hayyaḥaḏ), often combined with another term such as “the Counsel of the Community” or “the men of the Community.” Another common term is “the Counsel” (hā‘ēṣâ). The word also means “advice,” and is used in this sense, but terms such as “the Counsel of the Community,” “the Counsel of the Torah,” and “the Counsel of the Fellowship of Israel” indicate that it is also a proper noun. The term “the Congregation” (hā‘ēḏâ) is used in compound terms, both for Qumrân and for those outside. Compare the terms “the Congregation of Israel,” “the Holy Congregation,” and “the Congregation of God” with the terms “the Congregation of Belial,” “the Congregation of Men of Unrighteousness,” and the Congregation of Nothing.” Another term, also translated “congregation,” but preferably “the Assembly,” is qāhāl. This occurs alone, “the Assembly,” and in compounds, “the Assembly of God,” and it is also used for those outside: “the Assembly of the Wicked” and “the Assembly of Gentiles.” A very difficult term to translate is sôḏ, “council,” or “secret (council).” (For an excellent study, see H. Muszyński, Fundament, Bild und Metapher in den Handschriften aus Qumran [1975].) It occurs in compounds, “the Council of the Community,” “the Council of Truth and Understanding,” and “the Sons of an Eternal Council.” It, too, is used of those outside: “the Council of Violence,” and “the Council of Nothing and the Congregation of Belial.” The names give some idea of their self-image and of their attitude toward those who were not members of the community.

The use of the terms “Israel and Aaron” (CD 1:7) and “Aaron and Israel” (1QS 9:11) seems to be simply a reference to the community. There are indications, however, that a distinction between the priests (Aaron) and the laymen (Israel) was intended. The community is described as consisting of priests, Levites, and “all the people” (1QS 2:19–21), or “Israel and Levi and Aaron” (1QM 5:1), or priests, Levites, sons of Israel, and proselytes (CD 14:3–6). Such expressions seem to rule out the idea that the community considered itself a community of priests.

A particularly troublesome term is hārabbîm, which can mean “the many” (i.e., either the entire community or the majority of the community) or “the great ones, the chiefs” (i.e., a hierarchy in the community). The word occurs about fifty-six times in the DSS, about thirty-four times in cols 6–8 of 1QS, and with significant use in cols 13–15 of CD. Each occurrence must be studied carefully in context, for the word is used in every possible way.

D. Organization

Authority was committed to the priests, the “sons of Zadok” (or “the sons of Aaron”), but one priest seems to stand above the others, possibly the one called “Chief Priest” (1QM 2:1f). In CD 14:6–8 is a description of “the priest,” followed by one of “the examiner” (meḇaqqēr), which suggests a hierarchy of the offices. The examiner (or it may be translated “supervisor,” “superintendent,” “overseer,” “visitor,” etc.) was obviously of considerable importance. The word occurs fifteen times in CD, always in passages where the “many” are under discussion. His duties included the admitting of new members, instructing the Many in the works of God, restoring the wandering ones, hearing witnesses, arbitrating disputes, advising the priest in case of disease in the camp, and taking the oath of the covenant.

“Twelve men and three priests” (1QS 8:1) have important responsibilities, but it is not fully clear whether the “counsel of the community” mentioned immediately before this term is the name of this group or the name of the entire community. The language seems to mean that fifteen persons are intended, but some scholars make the “three” a sort of “inner circle” of the twelve and find a point of comparison with the disciples of Jesus. The “judges of the congregation” (CD 10:4) resemble the Twelve and Three, and one group may have developed from the other. In each case the laymen outnumber the priests: in the case of the judges, four were from the tribe of Levi and Aaron and six from Israel, or “up to ten men selected from the Congregation.” In 1QM, fifty-two “fathers of the congregation” are mentioned (2:1), and twenty-six “heads of the courses,” i.e., priests who rotate in the service (2:2, 4). Their duties are described in relation to the eschatological battle.

“The Prince of all the Congregation” is mentioned in connection with the star-and-scepter prophecy (Nu. 24:17) and identified with the scepter (CD 7:20f). The same title is found on the shield (?) of a person in the eschatological battle (1QM 5:1) and in the Benedictions (QSa1 5:20). It is not established that this person was then alive; rather, he appears to belong to the future and may be the messiah.

The order of precedence of the community is a point that recurs in various expressions, and “position” or “turn” was closely adhered to. The membership was mustered every year, and a member was advanced or set back in rank according to his deeds or his perversity (1QS 5:20–25). Members were listed by rank (“written by their names,” CD 14:3–6), and everyone knew the place of his standing and was expected to stay in that place (1QS 2:22f). Even in the smallest meeting of a minyan (ten men), they were to speak in order, “each according to his position” (6:3f). It seems clear that this rank was based on spiritual and moral behavior, and was not a matter of heredity — which may have been a protest against the aristocracy of the Sadducees.

Details of admission to the sect are spelled out in 1QS and QSa1. There was a year of testing, sometimes likened to postulancy, when one seeking admission was carefully examined. This was followed by a second year, likened to the novitiate, at which stage the person seeking admission became a member of the community but was not entitled to all its privileges. His wealth and his work were handed over to the Examiner, but were not to be used by the community until the novice had successfully completed his second year. At that time he was mustered “according to the mouth of the Many,” and, if the lot fell for him to “draw near to the Community,” he was written in the order of his position (1QS 6:13–33). The provisions in QSa1 1:19–21; 2:3–9 add other details, but these may apply to a smaller group within the community.

E. Daily Life

That Qumrân was a sectarian community that separated itself from Jerusalem Judaism cannot be disputed. Its relationship to other sects or “camps” is not so clearly defined. Specifically, the precise relationship of Qumrân to the Essenes is not known, so this description of life at Qumrân is limited to the DSS.

The members of the community “passed over” into the covenant and were not to turn back (1QS 1:16–18). They were to do good, truth, and justice, to walk before God perfectly, “to love all the sons of light … and to hate all the sons of darkness” (1:2–11).

The knowledge, strength, and wealth of each member was to be brought into the community (1:11–13; cf. 6:17, 22), and this communalism extended to much of the daily life, including common meals and common counseling (6:2f). The occurrence of the term “poor” (’eḇyôn) in a number of texts has led some scholars to conclude that the vows of poverty and celibacy were part of this “monastic” sect, but this conclusion gets little support from the texts. We may nevertheless infer that life at Qumrân was devoid of luxuries and was probably little above the level of poverty. On the matter of celibacy, there is likewise conflicting evidence. The texts state that women and children could be admitted to the community; cf. QSa1 1:4–12, where provision is made for their “entering,” and CD 7:6–9, where provision is made for marrying women and begetting sons. Nevertheless, the remains found in the cemetery and the rigorous life demanded by the location suggest that few women did in fact enter the community. If it was not a monastery de jure it seems likely that Qumrân was monastic de facto.

The community had gone to the wilderness to prepare the way of Hû’hā’ (a surrogate for the divine name, possibly an abbreviation of hû’ hā’ĕlôhîm, “He is God”), which was to be done by the study of the Law (1QS 8:13–16). In CD 6:4, the Law is associated with the very origin of the sect. But what precisely is meant by the term “Law”? An examination of the DSS will show that the positive virtues of the Mosaic law are stressed: truth, righteousness, kindness (ḥeseḏ), justice, chastity, honesty, humility, and the like. The most concentrated expression of these virtues can be found in the description of the conflicting “two spirits” (1QS 3:13–4:26). It is also possible to draw from the DSS a body of texts that will define works of the law as a legalism not greatly different from that of the Pharisees (cf. CD 9–16; 10:14–11:18 goes into great detail concerning the keeping of the sabbath).

The attitude of Qumrân toward the Mosaic sacrificial system is not clear. There is reference to sacrifices in 1QM 2:1–6, and reference to “the altar of burnt offering” in CD 12:8f. Nothing that appears to be an altar has been excavated at Qumran, however. (H. Steckoll announced the discovery of an altar at Qumrân in Madda‘, Jan. 1956, pp. 246ff, but de Vaux denied that the stone was an altar in RB, 75 [1968], 204f). There is no mention of sacrifices in 1QS and some scholars are inclined to date CD from an earlier, pre-Qumrân period. In fact, one passage in 1QS seems to put “the offering of the lips” and “perfection of way” in place of animal sacrifices “to make atonement for the guilt of rebellion and the infidelity of sin” (1QS 9:3–5). This would be in keeping with some of the attitudes toward sacrifices expressed by the prophets (cf. Isa. 1:12–20; Mic. 6:6–8; etc.); and it certainly must be recognized that diaspora Judaism had substituted prayer and good deeds (miṣwôṯ) for animal sacrifices even before the destruction of the Temple in a.d. 70.

The systems of aqueducts and cisterns at Khirbet Qumrân promptly led scholars to discuss whether this was a baptist sect. The use of the term “baptist” needs careful definition, for there were several contemporary types of baptist movements. (See J. Thomas, Le mouvement baptiste en Palestine et Syrie (150 AV J.-C. — 300 AV J.-C.) [1935].) Unfortunately, the texts of Qumrân do not spell out the details of their ritual washing, necessitating conclusions drawn only from negative statements. The bathing was a means of purification (CD 10:10–13), yet it did not have in itself the power of cleansing unless the sinner had repented of his wickedness (1QS 3:1–6). If “the Purity” refers to the water (cf. 1QS 5:13f), no postulant or novice could touch it (6:16f, 20f), but it is possible that the term applies to some part of a sacred meal. At any rate, we may safely conclude that baptism at Qumrân was not an initiatory rite (such as the baptism of John), but rather a ritual for purification reserved for members of the community who had the proper attitude toward the statutes of God (cf. 3:6–9).

The community observed the Jewish holy days, and the Day of Atonement was important in the history of the sect (1QpHab 11:7). Qumrân observed a different calendar from that of Jerusalem Judaism, or, more accurately, used both a lunar calendar of 354 days (like the “Jewish” calendar today) and a solar calendar of 365 days, similar to that of the book of Jubilees. The statement in 1QpHab 11:4–7 makes no sense unless the Day of Atonement was observed by the “wicked priest” on a different day from that which Qumrân observed. Considerable literature has appeared on the subject, some of which involves the problem of the date of the Last Supper in the Synoptics and in the Fourth Gospel. (For discussion and bibliography, see Fitzmyer, Dead Sea Scrolls, pp. 131–37.)

Certain texts indicate an annual examination of the members of the community in connection with the Feast of Weeks (cf. 1QS 5:24) or the Day of Atonement, at which time the promotions and demotions took place. Possibly at the same time the postulants and novices were examined (6:13–23). A detailed list of punishments and fines for offenses against the community is given (6:24–7:25), and for more serious offenses banishment (or excommunication) was a possibility (7:19–21), either for two years, or, in the case of one who had been a member for more than ten years, permanently (7:24f).

F. Doctrine of God

Since Qumrân was a Jewish sect with its roots in the Hebrew Scriptures, its doctrine of God is essentially that of Judaism. God is the God of Israel (1QS 10:8–11), the Lord of creation (1QM 10:11–15), the God of history (11:1–4), and in particular the God of the Qumrân covenanters (11:9–15; see also 1QH 1:6–20). Much has been written on “Qumrân dualism,” some of it with confusion of terminology. There is matter-spirit dualism, good-evil dualism of a personal, ethical nature, and cosmological dualism of two opposing deities in the universe, to mention only three categories. The Hebrew Bible knows nothing of philosophical matter-spirit dualism. Ethical dualism, on the other hand, is thoroughly scriptural (cf. Prov. 2:13–15; Jn. 1:5; etc.). Ethical dualism is found in the DSS, and can be summarized in the terms “sons of light” and “sons of darkness.” (For an extended passage, see 1QS 4:2–8.) But the doctrine of the two spirits (1QS 3:17–21), with its Angel of Darkness (3:21–4:1), together with the prominence given to Belial and Mastema in the DSS have led some to see a cosmological dualism in Qumrân, which is sometimes traced to Zoroastrianism. (For early discussions, see LaSor, Bibliography, nos 3130–3211.) It must be kept clearly in view, however, that true cosmological dualism starts with two coeval opposing deities, whereas the OT presents its God as the only God, the creator of everything and everyone else, including evil (cf. Isa. 43:10–13; 44:6–8, 24–28; 45:1–7; 46:8f). Even Satan is presented as operating only with God’s permission (cf. Job 1:6–12; 2:1–6). Likewise in the DSS, God is the only God. He created the two spirits (1QS 3:17, 25), and He has decreed their times and their works (4:25f). God is ruler over all angels and spirits, including Belial and Mastema (which seems to be another name for Belial; cf. 1QM 13:9–13).

G. Doctrine of Man

Although the last and highest being created, man was tempted and disobeyed God’s command. Thus the Hebrew Bible tells of God’s redemptive activity on behalf of sinful mankind, a concept that certainly underlies Qumrân anthropology. Like the canonical Psalmist, however, the Qumrânian was burdened by a sense of unworthiness and wickedness (1QS 11:9–15; 1QH 10:3–8, 12; 4:29–37; 9:14–18; 13:13–21; 18:21–29).

The Qumrân doctrine, however, seems to develop a more rigid concept of election, amounting almost to a “double predestination,” according to which God created the righteous from the womb for agelong salvation, but the wicked He created for the time of His anger (1QM 15:14–19; cf. 1QS 3:13–4:26). Possibly this is simply a rhetorical way of stressing the doctrine that man’s righteousness comes from God (1QH 4:30–33), for man’s responsibility to do good works is likewise emphasized (cf. 1QS 5:11f). In fact, any legalistic system (such as found at Qumrân) would have difficulty developing in a strongly predestinarian theology.

The emphasis on “knowledge,” “mysteries,” “truth,” and similar terms in the DSS has led some to see a kind of Gnosticism in Qumrânian beliefs. This has been beset by a marked imprecision in the use of the terms “gnosis” and “Gnosticism” (discussed at some length in LaSor, Amazing Dead Sea Scrolls [rev ed 1962], pp. 139–150). There is no philosophical dualism in the DSS, no demiurge or series of emanations, such as are a necessary part of classical Gnosticism. But the question of gnosis or secret knowledge of the “mysteries” of the system deserves careful study. The secret knowledge of Qumrân, revealed by God to the covenanters (1QS 8:11f; 9:17f; 1QH 1:21; 2:17f), concerns the community’s salvation in the end time (1Q27 5–8; 1QpHab 7:1–8; 1QS 4:18f; 1QH 11:3f, 11f). For fuller study cf. H. W. Huppenbauer, Der Mensch zwischen zwei Welten, Der dualismus der Texte von Qumran (Hohle I) und der Damaskusfragmente (1959).

H. Eschatology

The community believed it was the last generation, living at the end of the age (QSa1 1:1f; CD 1:10–13). The War Scroll (1QM) is a description of the final war, with the destruction of the gentile nations and the triumph of the people of the new covenant (i.e., Qumrân). In keeping with the eschatology of the Hebrew Bible, the community looked for a “day of vengeance” (1QS 10:19), a “day of slaughter” (1QH 15:17), a “day of judgment” (1QpHab 13:2f), by which God would be glorified (1QH 2:24). There would be suffering and distress for Israel, but destruction for the wicked (1QM 15:1f; cf. 1QH 6:29f). The language is graphic (cf. 1QS 2:5–9; 4:11–14; 1QH 3:29–36). Following the judgment would be a time of peace and blessing (1QM 17:7), of purification (1QS 4:19–34), and salvation (1QM 1:5). The people of God would live a thousand generations (CD 7:6), forming an eternal house (4QFlor [4Q174] 1:2–7).

The Qumrânian concept of the Messiah has been much discussed (see Fitzmyer, Dead Sea Scrolls, pp. 114–18; LaSor, Dead Sea Scrolls and the NT [1972], pp. 98–105). To carry on the discussion with some degree of precision, the term “Messiah” should be limited to the “son of David” who is to come at some future time to establish once again the kingdom of Israel and to usher in an age of righteousness and peace. This is the meaning of the term as used in “normative” Judaism. In Christianity the term “Christ,” taken from the Greek equivalent of “Messiah,” has become much more complex by incorporating the Suffering Servant and the apocalyptic Son of Man into the figure. Sectarian Judaism sought to avoid some of the complexities by adding a suffering “Messiah son of Joseph,” a Messiah from the tribe of Levi, and an apocalyptic heavenly being. How much of this expansion is found in Qumrân theology?

The “Messiah of Israel” is mentioned in QSa1 2:14, 27, and “Messiah” in QSa1 2:12. In the Patriarchal Blessings, the “Messiah of righteousness, the sprout of David” is mentioned (4QPBless 2–5) and in the Florilegium, the Davidic descent of the one who shall arise in the latter days is stated (4QFlor 1:11–13). There can be no doubt that the community looked for the Davidic Messiah. The more difficult question to answer concerns another messianic figure, or other such figures.

When the Damascus Document was first published a number of scholars suggested that the formula “the Messiah of Aaron and Israel” (CD 8:24 par 20:1; 12:23–13:1; 14:19) should be emended to read “the Messiahs of Aaron and Israel.” The expression “the Messiahs [or anointed ones] of the Holy One” is found in CD 6:12. When the Manual of Discipline was published, it was quickly noted that 1QS 9:11 reads “the Messiahs [in plural!] of Aaron and Israel,” which was taken as confirmation of the proposed emendations in CD. However, to take mešîḥê ’āharôn weyiśrā’ēl to mean one Messiah from Aaron (a priestly messiah) and a second Messiah from Israel (a lay Messiah) raises serious grammatical questions (LaSor, VT, 6 [1956], 425–29). Moreover, the expression in CD 8:24 (par 20:1) reads māšî (a)ḥ mē’āharôn ûmîyiśrā’ēl, “an anointed one from Aaron and from Israel”; in no way can this be made plural by simply emending a construct singular to construct plural. The evidence from 4QDb = CD 14:19 supports the reading in the singular, thereby denying the possibility of textual emendation of CD in the Middle Ages. The simple expression “the Messiah of Aaron” is never found in the DSS. For these reasons, a Messiah of Aaron per se cannot be found in Qumrân eschatology. A curious passage in the Order of the Congregation, however, refers to what has been called “the messianic banquet” (QSa1 2:11–23). Everything about the event seems to raise some question, particularly the words that prescribe the ritual for every assembly where ten men are present (QSa1 2:21f), and, except for the fact that the “Messiah” is present (QSa1 2:12, 14 [broken text], 20), it could hardly be called a “messianic banquet.” The most important point to be noted is that “the priest” or “the chief [priest]” at the ritual takes precedence over “the Messiah.” The concept of a priestly person of eschatological significance therefore cannot be entirely dismissed. (For the full text in translation with all restorations of the broken text indicated, see LaSor, Dead Sea Scrolls and the NT, p. 101.)

It is of primary significance that the apocalyptic “Son of Man” does not appear in the DSS. Eleven different MSS of Enoch are represented in the fragments from the Qumrân caves, representing all parts of Enoch except Book II (the Similitudes or Parables). Only in Book II does the figure of the Son of Man appear, and its absence from the DSS suggests either that it was composed at a later time or that it was deliberately excluded by Qumrân. Since apocalyptic elements are usually associated with sectarian Judaism (and indeed are absent from “normative” Judaism), and since such elements are supposed to have come into Judaism as a result of contact with the Zoroastrian religion, the absence of these elements from Qumrân eschatology becomes doubly significant. A number of theories about apocalyptic in general and about supposed Zoroastrian origins of Qumrân eschatology in particular need to be reexamined.

Attempts to identify other eschatological figures, such as “the seeker” (or commander or law-giver), the “prince of the congregation,” and especially the (or a) “Teacher of Righteousness” (see below), have found no general agreement.

I. Teacher of Righteousness

The term môrê haṣṣeḏeq “teacher of righteousness” or “righteous teacher” occurs seven times in the Habakkuk Commentary (1QpHab 1:12; 2:2; 5:10; 7:4; 8:3; 9:9f; 11:4f), once in 1QpMic 16, and once (partially restored) in what was formerly identified as 4QpPs37. The Damascus Document has several slightly different terms, namely, môrê ṣeḏeq, “a righteous teacher” (CD 1:11; 8:55); yôrê haṣṣeḏeq, “teacher of [or the one teaching] righteousness” (6:10f); môrê hayyaḥaḏ, “the teacher of the community” (8:23f); yôrê hayyaḥaḏ, “the one teaching the community” (8:36f); môrê, “a teacher” (8:51); and yôrêhem, “their teacher” (3:7f). In some of these passages the context indicates that the reference is not to the one generally identified as “the Teacher of Righteousness,” but to a future teacher, or in one instance (3:7f) to God Himself.

From these texts the following points can be established beyond reasonable doubt. In former times, men did not listen to their Teacher (probably meaning God) (3:7f). He punished them, but brought into being the community of penitents; after twenty years He raised up for them a teacher of righteousness (1:11). This teacher was a priest who was given understanding in order to interpret the words of the prophets (1QpHab 2:6–9; 7:4f), which would result in deliverance from judgment for the doers of the Law (1QpHab 8:1–3). The men of the community heeded his words (CD 20:27f, 31f). He was, however, opposed and persecuted, pursued and probably “swallowed up” by the Wicked Priest (1QpHab 11:4–8; 1:12), for which God allowed the latter to be humbled (9:9f). The “house of Absolam” (interpretation uncertain) did not help the teacher (5:9–12). The teacher of the community was “gathered in,” probably meaning that he died (CD 19:33–20:1, 13–15). The covenanters looked for “the rising of one teaching righteousness in the last days” (6:10f).

From this body of material, passages in the Hymns (1QH) that are believed to be autobiographical, numerous statements or beliefs about Jesus, and good imaginations, scholars have built up a composite picture of the Teacher of Righteousness that fills many volumes. This, however, is not to reject scholarly efforts to sift probabilities and possibilities from the DSS. It is not established that the Teacher of Righteousness was the author of any of the Thanksgiving Hymns (1QH). The Teacher is not mentioned in a single psalm, nor is he elsewhere identified as a “psalmist” or by any equivalent terms. On the other hand, the Teacher is recognized as one whom God caused to know the mysteries of the words of the prophets (1QpHab 7:4f) and one who was the target of abuse and persecution by the Wicked Priest (11:4–8; 5:9–12). The Teacher was not the founder of the movement (he was raised up twenty years after its beginning; CD 1:8–11), but he was appointed by God to build the congregation of His elect (4QpPs37). Therefore the Teacher must be recognized as one of the significant leaders in the community, probably the most significant of its spiritual leaders in its earlier days, and possibly the only spiritual leader of any stature in the entire history of the sect. It is entirely reasonable to assume that some, if not all, of the Hôdāyôt were either composed by the Teacher or inspired by him (“inspired” in its common and not its specialized theological sense).

The task, then, is to apply critical methods to the fantastic claims made by certain writers, and to separate what is clearly false from what is reasonably possible. This may be summarized in a simple statement that needs to be amplified by careful scholarship: any element in the reconstructed life of the Teacher that can be traced to NT statements about Jesus, but which has no textual support from the DSS (such as the virgin birth, the atoning death, the crucifixion, the resurrection, and the second coming of the Teacher of Righteousness), must be suspect and is probably to be rejected. (Such a textual study of the major problem areas has been attempted in LaSor, Dead Sea Scrolls and the NT, pp. 106–130. See also H. H. Rowley, The Dead Sea Scrolls and the NT [1957]; BJRL, 44 [1961/62], 119–156; 40 [1957/58], 114–146; 49 [1966/67], 203–232.)

III. Significance of the Scrolls

Assessment of the values of the Qumrân discoveries must be limited in this article to the areas relevant to biblical studies. These may be grouped as: text and canon of the OT; developments in early (“intertestamental”) Judaism; and relationship to the NT.

A. Text and Canon

Prior to the discovery of the DSS, witnesses to the OT text and canon were principally the following: (1) the so-called Masoretic Text of the Hebrew Bible, which could more accurately be designated the received consonantal text and the text with vocalization and other pointing by the Masorites (MT) — they should not be confused, for the consonantal text is several centuries older than the MT; and (2) translations, such as the Septuagint (LXX) and Jerome’s Vulgate. Other witnesses of significance included the Old Latin, the Syriac, the Samaritan, and other versions. The oldest extant Hebrew text was no earlier than the 10th cent a.d., but the versions give evidence that goes back to the 5th cent a.d. (the time of Jerome’s work) and to the 2nd or 3rd cent b.c. (the time of the LXX). With the discovery of the DSS there is primary evidence, not merely that of translations, that goes back to the 1st and 2nd (and possibly even the 3rd) cents, b.c.

The text of the biblical MSS from Qumrân may be divided into two main categories. In one group are those portions that agree within reasonable limits with the consonantal text. (Since the DSS texts are not vocalized, they cannot be compared with the MT.) By “reasonable limits” is intended the inclusion of orthographic differences (such as hw’h for hw’, lw’ for l’, etc.) that do not present any significant difference in the text. The second category includes those readings that clearly are not in agreement with the consonantal text. This second group could be further subdivided into readings that agree with LXX but differ from the consonantal text, and those that differ from both. Published studies indicate that certain OT books, such as Genesis, Deuteronomy, and Isaiah, are textually much closer to the consonantal text that others, such as Exodus and Samuel. The evidence leads to the conclusion that there were in existence in the first cents b.c. and a.d. at least three Hebrew text-types: the received text that formed the basis of the consonantal, the text that was used for the Greek translation, and a text that differs from both of these.

This conclusion should cause no surprise, for it was already indicated by at least two lines of evidence. The witness of NT quotations of OT passages indicates that some quotations can be traced to the Hebrew Bible (received text), some to the Greek version, and some to neither of these (the third text). It has sometimes been the practice to consider this third group of NT quotations as “loose dealing” with the OT text, but it is open to question whether a writer seeking scriptural authority for his statement would be allowed to handle the biblical passages with such abandon. The second line of evidence comes from Jewish tradition, where the formation of the “received text,” often but questionably traced to the Council of Jamnia (sometime after a.d. 90), is described as taking the reading of two witnesses against one (Taanith iv.2; Sopherim vi.4; Siphre 356), in other words, working from three texts or text recensions that were in existence at the time.

This should lead, once and for all, to the rejection of the view that “only the MT” is inspired and to be considered the authoritative reading. While it is true that in most cases the reading of the MT is to be preferred, it is also true that each reading must be studied in the light of the available witnesses to the text.

A much more difficult problem exists with regard to canon. The presence of a certain writing in the DSS is certainly no indication that the community considered that writing canonical. The evidence of the pešārîm (“commentaries”) indicates that only the books of the Hebrew Bible—and not all of them, by any means — were studied and commented upon. Arguments in support of the “Protestant” canon have at times included the claim that only those books written in Hebrew are canonical. But the discoveries at Qumrân call into question the validity of this argument, for fragments of a Hebrew text of at least one of the deutero-canonical books (4QTob hebra) have been found.

As a matter of fact, it can be seriously questioned whether we can dismiss so summarily the noncanonicity of books in the Qumrân Library. Since it was the library of a sectarian group, and not a public lending library or a resource library for scholarly research, we must ask why certain works were found there and why others were not. Perhaps a strict definition of “canon” cannot be insisted upon for Qumrân. We may have to accept the simple fact that these were the books that the community considered significant for them. The canonicity of Esther is not called into question by its absence from a sectarian library, nor is canonicity established for a work like Jubilees (of which more MSS were present in the DSS than of some biblical books). There is a subjective element in canonicity, for the term means “those books which are considered by a group to be authoritative.” There is also an objective element, for divine origin alone is the basis for divine authority. Qumrân obviously recognized the divine authority of the Law, and the members set themselves to study it and put it into practice. Likewise, they recognized divine authority, or at least divine mysteries, and believed that special knowledge had been given by God to the Teacher to interpret these mysteries. There are interpretations of Psalms as well as of a number of the Prophets in the DSS. The adherence at Qumrân to the calendar of Jubilees, plus the presence of a considerable number of MSS of Jubilees, brings into focus the question of whether we can objectively establish canonicity for that group, or for any other group. “The inner testimony of the Spirit” may well be the principal basis for canonicity.

B. Developments in Early Judaism

The relevance of the rise of Judaism to biblical studies may not be readily understood, but just a few facts should clarify the matter. By any but the most extreme critical positions, the OT was completed at least two centuries before the writing of the earliest NT book, and more probably three or four centuries before. Much can happen in that period of time. For example, the word “Messiah” as a term denoting the coming eschatological son of David does not occur in the OT. (In Dnl. 9:25f, the word lacks the definite article and simply means “an anointed one.”) Yet by the time of Jesus’ birth, the term was widely used by Jews and had a fairly well defined meaning, so that both John the Baptist and Jesus could be asked, “Are you the Messiah?” (cf. Mt. 26:63; the question is implied by John’s answer in Jn. 1:20, cf. v 25). The concept of the Messiah, though rooted in the OT, took its NT form in the intertestamental period.

At the change of the eras, the 1st cents b.c. and a.d., the Jews were not a homogeneous people, ethnically, socially, or religiously. The Dispersion was already several centuries old, and Jews were scattered far and wide. Some were strongly hellenized. Synagogues existed even in Jerusalem — by tradition, 480 of them (T. P. Megillah 73d). There were several Jewish sects, including the Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes, Christians, Ebionites, and others. Epiphanius (ca a.d. 375) listed seven Jewish sects, and R. H. Pfeiffer adds four Samaritan sects. The sects were marked by differences; their common Judaic tenets were what identified them as Jews. The NT mentions only the Pharisees and Sadducees (the Zealots were a political movement, rather than a religious sect). With the discovery of the DSS, some scholars identified the community as Essenes, naively viewing that as the only alternative to their being Pharisees or Sadducees.

Practically all that is known about the Pharisees and the Sadducees comes from two sources: Josephus and the NT. All that is known about the Essenes comes from Philo, Josephus, and Pliny the Elder. (Hippolytus of Rome drew from Josephus.) The relationship of the Essenes to early Christianity has been discussed at various times. A fairly full treatment, including a study of the suggested etymologies of the name “Essene,” can be found in J. B. Lightfoot, St. Paul’s Epistles to the Colossians and to Philemon (1875), pp. 82–95, 114–179. All the relevant texts from Philo, Josephus, and Pliny can be found in Dupont-Sommer, Essene Writings from Qumran, pp. 21–38.

That there are many points of similarity between the Essenes and the Qumrân community is beyond question. There are also serious points of difference. The differences could be explained by saying that the DSS are the primary sources for knowledge of the Essenes, whereas the other writings are only secondary material and that Philo, Josephus, and Pliny therefore must be corrected by the statements in the DSS. But this method is flagrantly circular reasoning, for it assumes what it sets out to prove, namely that the Qumrânians were Essenes. Another way of explaining the differences is to introduce elements of time and geography. Josephus writes that he was determined to know the three Jewish sects at first hand, and therefore planned to join each in turn. He joined the Essenes when he was sixteen, but since he was already a Pharisee at nineteen, it is certain that he had time only to meet the entrance requirements of the Qumrân group. It is known that Qumrân was only one of several “camps” of the covenanters (CD 14:3, 7–11), and some possibly did not live in camps (cf. 7:6–9). Also it is known that the Essenes left the cities and dwelt in towns and villages (Philo Quod omnis probus liber sit 75, cf. Apologia 11.1; Josephus BJ ii.8.4 § 124). Since Josephus was born in a.d. 37, he was sixteen in a.d. 52/53, and the writing of his account was decades later. It is therefore highly probable that he belonged to an Essene group other than that located at Qumrân (if indeed Qumrân was Essene), and he certainly was separated by at least several decades from the time when CD and 1QS were first formulated. We therefore must reckon with the possibility of developments in Essenism. It is also possible that the Essenes and the Qumrânians were separate groups or sects that split from a common source sometime in the 2nd cent b.c. (see LaSor, Dead Sea Scrolls and the NT, pp. 131–141). But whether the Essenes and Qumrânians were of the same sect or divergent sects from a common origin is of little import for the present discussion. What is important is to note that Judaism was a house divided, and that Jerusalem Judaism was severely criticized not only by Jesus but also by the Qumrânians. G. F. Moore distinguished “normative Judaism” from “sectarian Judaism” (Judaism, I [1927], 3). Some modern Jewish scholars object to this distinction; S. Sandmel prefers to speak of “Synagogue Judaism” as distinguished from “Temple Judaism” (Judaism and Christian Beginnings [1978], pp. xvii, 10f). Whatever terms are used, Judaism cannot be treated as a monolithic structure, and interpretation of parts of the NT requires a more careful study of the various forces that were at work in early Judaism. Some of the concepts in Paul’s writings, for example, which have long been held to be reactions against a second-century Greek type of Gnosticism, may now be viewed as possibly having their origins in Jewish sectarian movements.

Especially in the area of Jewish eschatological or messianic thought and in the development of apocalyptic concepts do NT students need to study Jewish materials, both rabbinic and sectarian. Here the Qumrân documents are helpful. There were Jews living in the 1st cent b.c. who were looking for the Messiah; the Qumrânians believed that they were in the last generation. The rise and sudden acceptance of John the Baptist is not at all incredible, when seen against this background. The attribution to Jesus of messianic terms, although He made no such claims in His early public ministry, and forbade men to say that He was the Messiah, must likewise be viewed against this eschatological fervor. Again, the expectation of Jesus’ disciples that He was about to restore the kingdom to Israel is part of the spirit of the times that is also found at Qumrân. The DSS in no way undermine the uniqueness of Jesus Christ, but they do help define more precisely wherein that uniqueness lies.

C. Relationship to the NT

A question often asked is, “Why were there no NT writings among the DSS?” Some NT fragments were found at Khirbet Mird, when the general search for caves took place following the Qumrân discoveries, but these clearly belonged to a later period (5th to 8th cent a.d.) and came from the ruins of a Christian (Byzantine) monastery. It is unfortunate that they were ever connected with the Qumrân discoveries in written accounts. There was also the claim that fragments of the NT had been found in Cave 7. (See J. O’Callaghan, Biblica, 53 [1972], 91–100; there has been no marked scholarly acceptance of his claims. For bibliography, see Fitzmyer, Dead Sea Scrolls, 119–123.) Given the dates of Qumrân (ca 140 b.c.–a.d. 68), the dates of the earliest NT writings, and the places to which they were addressed (those written before a.d. 68 are probably 1 and 2 Thessalonians, Galatians, Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, James, Paul’s prison Epistles, and possibly the sources of the Synoptics), there is little reason to suppose that any of them would have reached Qumrân. Moreover, this was an exclusivist sect, according to its own words, and would have had little or no interest in another Jewish sect.

The claim has sometimes been made that John the Baptist received his training at Qumrân. This may be supported by two lines of reasoning, first, that John was brought up in the Wilderness of Judea until he began his ministry (cf. Lk. 1:80), and second, that John’s ministry, with its denunciation of sinners, its call to repentance, its quoting of Isaiah, and the central place of baptism, seems to have some relationship with Qumrân. These points may be refuted. John’s parents were part of the Jerusalem religious group against which the Qumrânians hurled invectives; Zacharias was a priest. Would he and Elizabeth entrust their only son, for whom they had waited so many years, to such a hostile group? John’s ministry was indeed a fiery one, but could that not have been influenced by the OT prophets rather than by Qumrân? John’s baptism was clearly initiatory: it was administered at once to anyone who repented. Qumrân baptism was certainly not that, but was rather a cleansing rite reserved to members who were scrupulous in their observance of the Law. John’s attitude was open and sinners were invited, even urged, to repent. The Qumrânians proclaimed a curse on anyone who made the truth known to the “sons of darkness.”

The claim has likewise been made that Jesus studied at Qumrân. A long list of similarities between His teaching and the writings from Qumrân can be compiled, and many scholars have contributed to such a list. It can be said as a general rule that these points can all be traced to the OT or to early Judaism. In no single case does Jesus seem to show clear-cut dependence on Qumrân. Moreover, the suggestion that He studied at Qumrân is highly improbable. Some of the same objections set forth against identifying John with Qumrân can be used in the case of Jesus. In addition, there is the psychological objection that the people of Nazareth were caught completely by surprise at the beginning of His ministry, for they knew Him and they knew His family. As for the extravagant claims that Jesus “appears in many respects as an astonishing reincarnation of the Teacher of Righteousness” (A. Dupont-Sommer, Dead Sea Scrolls [1952], p. 99), and the labored efforts to show that every major fact in Jesus’ life can be traced to a similar point in the life of the Teacher of Righteousness, these have been refuted by careful scholars many times. (See LaSor, Dead Sea Scrolls and the NT, pp. 117–130, 206–236, and footnotes. See especially Rowley’s works, mentioned above, and his exhaustive bibliographical references.)

Several studies have been published in which certain Pauline ideas have been compared to statements in the DSS. Some of the parallels have been made by scholars who would deny Pauline authorship on critical grounds to the very works that they quote, namely, Ephesians, Colossians, and the Pastorals. Such scholarship does not commend itself. There are, however, several points at which the Qumrân writings help scholars understand the development of ideas in early Judaism, and see that some of these ideas could lie behind some of Paul’s statements. Paul is a curious mixture of what Sandmel calls “Temple Judaism” and “Synagogue Judaism,” being both a strict Pharisee and also a native of the Hellenistic world. To see Paul as only a Hellenist Jew, and to fail to see the complexities in Judaism, is to take a somewhat distored view of both. (For fuller discussion, see articles on the subject in K. Stendahl, ed, The Scrolls and the NT, [1957], notably those by W. D. Davies and K. G. Kuhn; see also J. Murphy-O’Connor, ed, Paul and Qumrân: Studies in NT Exegesis [1968].)