Jacob was an OT patriarch, son of Isaac and father of the twelve eponymous ancestors of the tribes of Israel.

The history of Jacob’s life has been preserved in Gen. 25–50. There are many opinions about the form and compilation of these stories (see V below), but for the purposes of this study they will be considered as authentic records of historical events. A century of archeological exploration, combined with the study of documents from the period in which the patriarchs must have lived, has shown that Genesis reflects accurately the social conditions of the time. This information enables parts of the biography of Jacob to be better understood. Evidence quoted as contemporary with Jacob is taken from material of the 18th and 17th cents b.c.

Significance of the Name “Jacob”

Two other names from the same root are found in the OT, Akkub and Jaakobah. It has long been known that a similar name was also in use in ancient Babylonia. Further discoveries of many more contemporary documents indicate that it is one of a large group of names borne by the West Semites who gained control of Mesopotamia at the beginning of the 2nd millennium b.c. “Jacob-el” (ya˓aqub–il) occurs not only in Babylonia (e.g., Kish and Khafadje) but also on the mid-Euphrates at ˓Ana and in the north at Chagar-Bazar. Several other names with the same root are recorded from Mari and other sites. Egyptian sources provide contemporary examples of Asiatic slaves with Semitic names, including some formed from ˓āqaḇ. An inscription of Thutmose III (ca 1450 b.c.) mentions a place in Palestine named ya˓aqub-el. One of the major rulers of the Hyksos period was named ya˓aqub-her. At a later period such names are found in the Palmyrene inscriptions.

The root ˓qb, meaning “heel” is found in Arabic and Assyrian as well as in Hebrew. From this basic noun was derived a simple verb “follow closely,” with various nuances. In Jer. 9:4 it has the connotation of “overtaking” (cf. 17:9; Ps. 49:6 [MT 7]). Yet it may equally have a more favorable significance, “follow closely” and then “guard, protect,” as in Sabean (cf. Job 37:4, “restrain”).

There can be little doubt that the name ya˓aqub-il had the sense of “protection,” perhaps as a prayer uttered at the birth of the child, “May God protect (him)” (so FSAC, p. 245). “Jacob” would be an abbreviated form of the name. According to G. R. Driver (Problems of the Hebrew Verbal System [1936]), however, ya˓alquḇ can be interpreted as a past tense as well as an imperfect (future). “God has protected” is a plausible translation of the name, one especially suitable if the birth had been difficult (cf. Gen. 25:22). In Jacob’s case the circumstances of his birth were likely to give rise to an allusive wordplay upon a current name, for he “grasped the heel” of his brother (25:26).

The Life of Jacob

“A wandering Aramean was my father” (Dt. 26:5). This is an apt description of Jacob’s history, which may be considered in four sections according to his place of residence.

Early Life in Canaan

The conception of Isaac’s sons is remarkable in that it did not occur until twenty years after his marriage to Rebekah. As Abraham had been required to exercise faith in the promise of an heir, so was Isaac. The peculiar nature of his birth may have given Jacob his name, but even earlier he was designated as the chosen son through whom the promise given to Abraham should pass. Although born in Canaan, he was racially distinct, being the grandson of a man from Ur of the Chaldees, a Semite among the descendants of Ham.

The relationship of Esau and Jacob, twin brothers and full-born sons of Isaac, could not be eased by such a separation as divided Isaac and Ishmael. Later teachings (e.g., Mal. 1:2f) show that it was by the sovereign will of God that one was chosen over the other. The supremacy of God over human customs was exemplified by the choice of Jacob, the younger son. The contrast between the two brothers may be seen as the contrast between the agriculturalist and the nomad-hunter who lives “from hand to mouth.” These were the characteristics of the later nations of Israel and Edom. Esau’s thoughtlessness lost him his birthright (the privilege of the firstborn son to inherit a double share of the paternal estate), thus allowing Jacob the material superiority. His equally heedless marriage to local women of Hittite stock (Gen. 26:34) rendered him unsuitable to become the father of the chosen people. Nevertheless, Isaac intended to bestow the blessing of the firstborn upon Esau.

The oracle given to Rebekah before the birth of her sons (25:23) probably encouraged her to counter Isaac’s will and to gain the blessing for her favorite son by a fraud. The blessing that was given to Jacob conveyed the status of head of the family, apparently apart from the status of heir. Esau had disposed of this many years before, an action comparable to the sale of a birthright recorded at Nuzi. The blessing, once pronounced, was irrevocable; and so Jacob was sent to the safety of Rebekah’s home until Esau should forgive him.

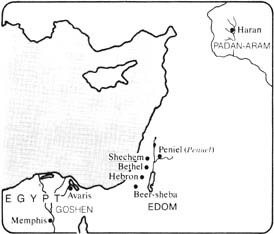

To Paddan-aram

Jacob was well over forty years old when he left home, for Esau had already married at the age of forty (Gen. 26:34; 27:46). The journey from Beersheba may be reckoned, however, as the commencement of his life as an individual. He had received the paternal blessing, and doubtless knew of the God who had made great promises to his father and to his grandfather; yet it was not until he slept at Luz that he realized that he was required to participate in the fulfillment of these promises. He was following the road to the north along the central hills when night fell, and he lay down with a convenient stone as his pillow. The text does not indicate that he had arrived at a recognized shrine, although Abraham had built an altar in that region (12:8) and archeological evidence suggests that it was an ancient holy place (see Bethel 1). In the dream God revealed Himself to Jacob and renewed the promise to him by His name Yahweh, the name in which the promise had first been given. The traveler was given reassurance for his journey and of his eventual return. The erection of a stone pillar, in this case only a small boulder, was a common practice for the commemoration of some notable event. For Jacob this place was henceforth sanctified as “the gate of heaven” where God first communicated with him. It was for him Beth-el, “the dwelling of God.”

Jacob moved northward to the “fields of Aram” (see Paddan-Aram). The relatives of Bethuel were evidently prosperous citizens of Haran who cultivated the land surrounding the town in the valley of the Jullab and pastured their flocks on the hills. Jacob was welcomed into his mother’s family. An agreement was made that he should give seven years of service and then take as his wife his cousin Rachel, whom he had first met at the well outside the town. A partially comparable transaction is known from Nuzi, where a man entered into servitude for seven years in return for a wife; but there the marriage probably took place at the beginning of the time. When the day of Jacob’s marriage arrived, Rachel’s father Laban substituted his elder daughter Leah, on the plea of a local custom that the elder was always wed first. Perhaps the narrator knew of another reason: Leah had “weak eyes” (Gen. 29:17), i.e., she was not beautiful, so it might have been more difficult to find a suitable husband for her (cf. E. Speiser, comm on Genesis [AB, 1964], p. 225). After the week of celebration had passed, Rachel also was given to Jacob. He had to promise another seven years of service in return. Jacob remained in Laban’s employ for six years after he had worked out his contract in order to earn sufficient capital for the support of his family.

Leah bore his first four sons (Reuben, Simeon, Levi, and Judah). Rachel, jealous of her sister since she herself was barren and eager to remove that reproach, gave her maid Bilhah to her husband. By this means, which was an accepted practice at the time (cf. Abraham and Hagar), any child born would be counted as Rachel’s (note 30:3). The two sons borne by Bilhah were named by Rachel, as if they were her own, Dan and Naphtali. Leah then did likewise with her maid Zilpah, who bore two sons, named by her mistress Gad and Asher. At this juncture Reuben, Leah’s firstborn and now about twelve years old, found mandrakes, which he brought to his mother. Rachel purchased this herb from her sister for its supposed aphrodisiac qualities. As a result of the bargain, Leah bore two more sons to Jacob, Issachar and Zebulun, and at some time a daughter Dinah. Then at last Rachel gave birth to her first son Joseph.

Now Jacob pressed for permission to return to Canaan. Laban could not afford to lose so good a herdsman and offered him any wage he cared to name. Yet even when Jacob had suggested his reward, Laban tried to avoid payment. The evasion was overcome by Jacob’s experience with the flocks. He succeeded in breeding fine sheep of the type he had asked from Laban, while his father-in-law was left with inferior stock. This prosperity aroused the jealousy of Laban’s own sons and of Laban himself. Rachel and Leah supported their husband when he related to them the divine command to return to his father’s home. They claimed that their father had not given them any dowry but had spent it instead, treating them as foreigners.

Return to Canaan

Jacob departed while Laban and his sons were away shearing sheep in the hills. Thereby he gained a two-day head start, and it was not until he reached the highlands of Gilead that Laban overtook him. The seven days indicated as the time taken by Laban’s party to cover about 650 km (400 mi) from Haran to Gilead are within the capabilities of good riding camels (see Camel). Jacob, with his family and his flocks, took a little longer. Laban complained that he had had no opportunity to bid farewell to his daughters with the accustomed feasting. More important, he wanted to find the “gods” that had been stolen (31:30, 32). These “gods” (Heb terāp̱îm, 31:19, 34) were almost certainly small metal or terra-cotta figures of deities such as are commonly found in the ruins of ancient towns. Possession of these images was vested in the head of the family, according to evidence from Nuzi. Certain texts specify that they are to pass to the son of the owner upon the latter’s decease, rather than to an adopted son, even if he has been made principal heir. Rachel’s theft can now be seen as an attempt to obtain for her husband the status of head of the household. Laban’s anxiety arose partly from this consideration and partly from the loss of the magical protection they were thought to afford. This value may well have been in Rachel’s mind, too, as she look them with her at the outset of a long journey. Divine command prevented Laban from using force against Jacob, and his daughter’s ingenuity deprived him of his gods.

No fault could be found in Jacob’s conduct in Haran either. In his own defense (31:36–42) he mentioned that he had not eaten any of Laban’s rams and had himself replaced those animals seized by wild beasts. Records from Nuzi describe the prosecution of shepherds who had made their own use of their masters’ flocks. The Babylonian laws of Hammurabi (ca 1750 b.c.) impose a fine of ten times the value of the animal taken on a shepherd convicted of such an offense. By the same laws, however, the loss of an animal killed by a marauding lion is to be borne not by the herdsman but by the owner (§§ 265–67).

Laban could do little but suggest a pact of friendship with his son-in-law. He proposed as terms of the treaty that Jacob should neither ill-treat his wives nor marry any other women, a clause often found in marriage records of this time. Moreover, the site of the covenant was to be a boundary which neither party should cross with evil intent. Ancient treaties frequently stipulate that rulers of states should not permit raids from their territory into the neighboring country and that they should be responsible for the punishment of any of their subjects who did so raid. Such treaties were solemnized by the naming of various important deities as witnesses and the deposit of a copy in a temple (see Covenant [OT] II). The covenant of Jacob and Laban was ratified solely by the invocation of the God of Abraham and of their common ancestor Terah. If either Jacob or Laban broke the terms of the agreement, the curse of God would fall upon him. The cairn and the pillar were visible expressions of the treaty, reminding them of it if ever they passed that way again. Stone slabs, simple boulders, rough-hewn monoliths, and carefully carved stelae have been discovered throughout the ancient Near East. Some are isolated on a hillside; some are grouped in a shrine or temple; all originally commemorated a notable event or person. When a treaty was to be recorded, a picture was carved, on some occasions, representing the contracting parties sharing a meal to indicate their unanimity and good faith, as Jacob and his kin ate together in Gilead (31:54).

The parting from Laban marked another stage in Jacob’s development. He was now head of his own household. He also climbed to a higher plane of spiritual experience. An encounter with angels at Mahanaim impressed upon him the might of the God who protected him, encouraging him for the journey southward to meet Esau. His brother’s seemingly hostile advance prompted a call for clear evidence of God’s guarding. Shrewdly, he sent a handsome gift to his brother and strategically divided his retinue into two parts; so large had his following become that each would be able to defend itself, or to escape if the other was captured. When all had crossed the stream of the Jabbok, Jacob was hindered by a stranger. The two struggled without one gaining advantage on the other, until the adversary dislocated Jacob’s hip. The disabled man still refused to release his antagonist, but, clinging to him, demanded his blessing. This could not be given until the stranger knew Jacob’s name. By telling it, Jacob acknowledged his defeat. His opponent, himself incognito, could command him as an individual. He emphasized his superiority by renaming the patriarch. No longer was he the man whose name had an unfavorable connotation. He became Israel, the one on whose behalf “God strove” or “God strives” and with whom “God strove.” The withholding of the adversary’s name, perhaps, caused Jacob to realize whom he had met. So Jacob called the place Peniel (Heb penî˒ēl, “face of God”), “For I have seen God face to face, and yet my life is preserved” (32:30 [MT 31]).

Jacob’s fear of meeting his brother proved groundless. Esau was content to forget the wrongs of the past and to share his life with his brother. The juncture of their two households would bring them greater security and standing among the alien peoples around them. As two men of so contrary natures were unlikely to live together long in harmony, Jacob chose the better course in turning westward, leaving the road to Edom.

Succoth was the first halting place before the Jordan was crossed. The length of his stay there is not indicated. It may be that the cattle were breeding and it was necessary to stop and provide shelter (the “booths”) for them.

Now Jacob entered the Promised Land. It was a natural course for him to follow the valley of the Wâdī Fâr˓ah, which joins the Jordan almost opposite Succoth, and so penetrate into the hill country. In Canaan the patriarch was landless, a wanderer, the type of person called Ḫabiru, or ˓Apiru, in ancient texts (see Habiru). He traveled until he reached a place of good pasture where he might settle for a time. The town of Shechem was well established in the center of the area, and it was from the rulers of this place that Jacob purchased a plot of land on which he pitched his tent and built an altar. Inevitably the family chosen by God was brought into contact with the local population, of which the ruling class at least were apparently of non-Semitic, Hurrian stock (see Hurrians). The son of the city’s ruler was attracted to Jacob’s daughter and took her by force. Although the prince, Shechem, afterward made an honorable proposal of marriage, this act alone could not restore amity between the clans. Jacob’s sons demanded that the Shechemites be circumcised before intermarriage could be permitted. The narrator comments that the brothers “replied deceitfully” (34:13); therefore it may be supposed that they understood that more than a physical sign was required to distinguish the inheritors of the promise from their neighbors. The leading citizens of Shechem all followed their lord in submitting to circumcision, motivated, no doubt, by the possibility of absorbing the “Hebrews” and adding their property to their own. While recovering from this surgery, they were incapable of defending themselves against Simeon and Levi, who killed them to avenge their sister. This treacherous deed, however effective in overcoming the evil that caused it and in preventing the adulteration of the tribe, was roundly condemned by Jacob (34:30; 49:5–7; cf. 34:31).

For safety’s sake, Jacob had to leave the domain of Shechem. He was instructed by God to return to Bethel and to sacrifice there. All danger of evil influence from Canaanites, Arameans, or other pagan peoples was left behind at Shechem. The journey was accomplished in peace; Bethel itself was outside the jurisdiction of Shechem. The promise given to Jacob fleeing to Paddan-aram was confirmed to Israel returning to the land of the promise. As he had done previously, Jacob set up a memorial stone, making a libation and anointing it with oil.

A brief note records the death of Rebekah’s nurse at Bethel. Evidently she was going with Jacob in the hope of meeting his mother at Hebron. A greater sorrow befell Jacob at Ephrath, for there Rachel died while giving birth to her second son. To call him “son of my pain” (Benoni), as she did, would have stigmatized the child all his life. Jacob changed his name to the honorable “son of the right hand” (Benjamin).

At last the caravan reached Hebron. This was the family “home,” for it contained the cave Abraham had purchased to serve as his sepulchre. Together, Jacob and Esau buried their father. Esau returned to his Edomite hills, while Jacob took his place as head of the family in Canaan. In Gen. 37–50 the writer narrates events in the lives of various members of Jacob’s family, the children of Israel. Their father’s biography can still be traced through theirs, however, for they were still dependent on him.

In Hebron Jacob lived as he had in Haran, sowing crops each year and pasturing his flocks wherever there was good grazing, even as far away as Dothan. His sons grew up, married, and begot children of their own. The favorite son was, naturally enough, Rachel’s firstborn, Joseph. His sale into Egypt (see Joseph II.A) was the consequence of the treatment his father lavished on him. After Joseph’s disappearance from home, his brother Benjamin became his father’s dearly loved son.

Famine had driven Abraham to Egypt, and Isaac had intended to make the same journey. Similarly, Jacob sent to the Egyptian granaries for corn when he was in want and presently left Canaan with all his immediate family to settle in Goshen. Every major change of Jacob’s life had been marked with God’s approval. On this occasion Jacob sought reassurance when he reached Beer-sheba, the place near the border of Canaan where both Abraham and Isaac had met with God (21:33; 26:23–25). The promise given to Jacob reiterated the promises of Bethel, that he would be the ancestor of a great nation which would return and possess the land, even as he himself had returned from Paddan-aram.

To Egypt

The caravan passed from Gerar along the main route to Egypt until it came to Goshen, the fertile area E of the Nile Delta. Here Joseph had arranged for his father’s family to settle. As Israel arrived in Egypt they must have appeared like the figures painted in a noble’s tomb at Beni-hasan ca 1800 b.c. (see ANEP, no 3), their curly black hair and beards and their long, colored tunics contrasting with the shaven heads and linen kilts of the Egyptians. Visitors and settlers from Palestine were no novelty. A list of slaves in an Egyptian household of ca 1740 b.c. included a number of Asiatics bearing Semitic names. Among them are some formed from the same verbal roots as the names of the family of Israel (e.g., škr, cf. Issachar, ˒šr, cf. Asher; cf. W. F. Albright, JAOS, 74 [1954], 222–233). At the close of the 18th cent b.c. the native rulers in Lower Egypt had been ousted by the Hyksos invaders from Palestine and Syria. These people dominated the whole country until their expulsion ca 1567 b.c. Evidence suggests that Jacob entered Egypt during the earlier phase of Hyksos rule, roughly ca 1700 b.c.; but this cannot be established with certainty. At that time the royal residence was either at Avaris (Tanis) or at Memphis, within easy reach of Goshen, as Gen. 46–47 suggests. Jacob was introduced to the court, where the pharaoh, with true Egyptian courtesy, inquired about his age.

As Jacob felt death approaching, he made arrangements for the inheritance of his property. Reuben, Jacob’s eldest son by Leah, had disqualified himself, as far as his birthright was concerned, by his sin (35:22). Rachel’s son stood far higher in his father’s eyes than any of the sons of Leah, and so it was to Joseph that the extra portion was assigned (48:22). In addition Joseph’s two eldest sons, Ephraim and Manasseh, were adopted by their grandfather as his own sons. This action may find a later parallel in a document from Ugarit recording the adoption by a man of his grandson as his heir, but in that instance he was the sole heir. Numbers of ancient wills have survived in written form, but there is evidence that oral dispositions were equally valid in law if duly witnessed. The complete control of the testator over his bequests and his ability to show favor or disfavor are clearly shown in the testament of a Hittite king, Ḫattusilis I (ca 1650 b.c.). Several of the king’s sons had rebelled against him, so a nephew was adopted as successor. He, too, made plots against the king, who eventually designated his grandson (?) Mursilis as his “son” while he, the king, lay dying.

The poetic form of the Blessing of Jacob doubtless enabled each of its hearers to remember the pertinent passage easily. The subsequent history of the several tribes is lucidly, and by divine inspiration, contained within the few lines of each section. There are no good grounds for doubting its authenticity, although the language may have been “modernized” by a later editor (as was done on occasion in Egypt). Through Jacob’s blessing the promise and covenant of God were no longer borne by one man in each generation. With the death of Jacob commences the history of the nation of Israel.

Jacob’s final injunction concerned his burial. His sons accordingly made their way back to Hebron and there placed his embalmed body in the cave Abraham had purchased as an earnest of his inheritance. All the pomp Egypt could muster was provided for the vizier’s father. The size and lamentations of this cortege so impressed the Canaanites that they named a place after it. So the “wandering Aramean” rested in his homeland.

Jacob’s Religion

Any attempt to study the beliefs of individuals apart from their life story is apt to become unbalanced. The stages on the road of Jacob’s experience of God have already been noted. As the religion of Israel and thus the roots of Christianity claim to derive from the patriarchs, it is necessary to attempt to understand Jacob’s spiritual life.

Background

The religious thought of the common people of western Asia at the time of Jacob can be discovered only from chance references in letters and other documents, and from material remains. Each city had its patron god associated with various minor attendant deities. Citizens could go to the major shrine or to smaller chapels to offer sacrifice or to join in the festivals connected with the particular cult. To what extent private persons could participate in the services of these temples is unknown. The life of the king depended largely upon the commands and wishes of the different gods as interpreted by their priests, who did not hesitate to threaten disaster if their desires were not met. Most of the individual’s devotion was paid to his “private” gods. It is likely that these were represented by small images kept in the house and passed from father to son (cf. II.C). Many cuneiform texts, notably but by no means exclusively the records of Assyrian merchants in Anatolia ca 1900 b.c., refer to the god of such a man or the god of his father. This is not evidence of monotheism — the same letter may contain a greeting, “May Ashur [the chief god] and your god bless you” — but of a choice and devotion to a single member of the pantheon. While the evidence is incomplete, it appears that the individual venerated lesser gods in his personal devotion while honoring as a citizen the local chief deity and naming his children after him.

Abraham left the multitudinous gods of Ur for the worship of the God who revealed Himself by the name of Yahweh. He was no minor god or even a leader among others; He alone was God. The simple term God (Heb ˒ēl) or the emphatic plural form (Heb ˒ĕlōhîm) sufficed to identify Him. Perhaps it was because the Canaanites placed a god ’El at the head of their pantheon that this title seldom appears alone. In the story of Jacob the names ’El Shaddai (43:14) and ’El Bethel (31:13; 35:7) occur together with Yahweh. They do not point to an underlying polytheism or a syncretism of local deities or clan totems. Each name has its own significance in the place it occupies.

Jacob’s Growth; First Crisis

Jacob’s religion can be viewed as consistent with the beliefs and practices of his fathers. No doubt he received some instruction from Isaac in the faith of the family, the history of Abraham, of the covenant, and of the promise. He first encountered God at Bethel, at the moment of greatest need in his life, fleeing from home to distant and unknown relatives. He received a vision of majesty, glorious and terrifying. Jacob saw the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, Yahweh Himself. God repeated to him the promise given to Abraham in Ur. His immediate reaction was to think that he had rested in a notable holy place (28:17). In the morning, however, he consecrated it by erecting and anointing the stone pillow. The name given expresses the significance of this place for Jacob. Above all else it was “the house of God.” It is not to be deduced that Jacob believed God to be confined to the stone or to reside therein, although such ideas are not unknown in the ancient world. Jacob returned to the place, but he also sacrificed and worshiped elsewhere. He vowed to take Yahweh as his God, if he should journey in safety and eventually return home. Moreover, he would devote a tenth of his income to God (cf. Abraham, Gen. 14:20).

Second Crisis

After twenty years in Paddan-aram came the command to return to Canaan. There could be no doubt of its authenticity, for it came in the name of the God of Bethel. The following events shed light on the beliefs of Jacob’s wives and their father. Already in the naming of their children Leah and Rachel had shown that they acknowledged Yahweh as God (Gen. 29:31, 33, 35; 30:24). Upon the announcement of the vision and of the order to leave home, they recognized it as God’s guidance (31:16). Their life and education among the pagans of Haran, however, had imbued them and their father with pagan superstitions. The family was thought to be protected by the presence of images of gods, the teraphim. Rachel’s theft of these laid the household in Haran open to the mischief of demons of disease and workers of black magic. Laban’s eagerness to regain possession of the figurines implied confidence in their power and apprehension at the disasters their loss might entail. The servants in Jacob’s train also brought images of their own. These were buried at Shechem before the visit to Bethel, together with earrings, no doubt decorated with heathen symbols (35:2–5). Yet Laban was not an apostate from the family religion. He attributed Jacob’s successes as a herdsman to the blessing of Yahweh (30:27), and he knew who it was that warned him not to harm Jacob (31:24, 29). Most significant is the oath he swore at Mizpah, invoking God as witness, the God of Abraham (Jacob’s grandfather), the God of Nahor (his own grandfather), and the God of their father Terah (31:50–53). The identity of the God of each generation in both branches of the family is proclaimed here. In this way the covenant was guaranteed by the witness of the Power proved constant by the ancestors of either party. Jacob added an oath by the “Fear” of Isaac. This epithet (31:42, 53) seemed to have been part of the personal relationship between God and Isaac. A different translation, “Kinsman,” has been proposed (FSAC, p. 248; but see Fear II.C). A single reference might admit of Jacob’s using a similar private epithet for God, “the Mighty One of Jacob” (49:24).

Third Crisis

The third crisis was the encounter at Peniel. Before Jacob met Esau he had seen the strength of his “Mighty One” in the angelic host at Mahanaim. Fear of his brother brought him to pray humbly for the protection of his father’s God. The plan he conceived for palliating Esau’s anger and for safeguarding his property was not allowed to supplant trust in God. The wrestling at the ford showed Jacob how weak he was before his God. It taught him the value of the continued prayer of one who is helpless. The awe that was aroused by the revelation at Bethel recurred as Jacob named the place, awe that a mortal should survive a meeting with God “face to face.”

Fourth Crisis

When Jacob setled at Shechem he built an altar to ˒El, with whom the local inhabitants might possibly identify their chief god. To emphasize the distinction Jacob called the name ˒El, God of Israel. There is no record of his erecting an altar and making a sacrifice — a natural sequel — before this time, apart from the sacrifice that solemnized his treaty with Laban (31:54). Here at Shechem he had become an independent man, head of his own family. The problem of Esau had been circumvented and Isaac was a very old man at Mamre. As the leader of the chosen race Jacob could offer sacrifices to God. He constructed another altar at Bethel when he went there the second time (35:1, 7) with all his household to worship. The promise given as he left Canaan a solitary fugitive was renewed now to Israel, father of eleven sons, head of his own family. All the experiences of the past had their culmination at this moment. The new name, plus the promise of nationhood and of the land, were confirmed by the God in whom Jacob had been taught to trust. Remembrance of this occasion was insured by the erection of another pillar and reiteration of the name Bethel, not in solitude but before many witnesses, notably his sons, who would remember its meaning.

Fifth Crisis and Triumph

The altar at Beer-sheba marked the final crisis. Here the patriarch worshiped for the last time in the land promised to him. This was the great test of his faith in God. As a counter to it he had the joyful anticipation of reunion with his favorite son. The piety of the elderly Hebrew is seen in his interview with the pharaoh. In the blessings of his sons is shown the mature expression of the patriarch’s trust in God, a confidence resulting from trying experiences. The immediate concern was the continuance of his name and that of his father (48:16), but he looked farther ahead to his children’s return to Canaan and to the part of each son’s family in the life of the clan. When viewed from the NT perspective, the blessing of Judah assumes greater import in its mention of the coming ruler. As the writer to the Hebrew church says, “By faith Jacob … blessed” (He. 11:21). What Jacob expected after his death is not revealed. He spoke of himself as “going down to Sheol” (37:35; 42:38), but this was no gloomy prospect after he had met Joseph and his two sons (48:11). The concluding phrase of the blessing of Dan (49:18, “I await thy salvation, O Lord!”) may hint at a deeper belief; it certainly implies great faith in God. Throughout his life his faith had grown, strengthened by the visions at Bethel. This was the faith he passed on to his sons, the outcome of his experience of the God who did not change, “before whom … Abraham … walked, … who has led me all my life long” (48:15). No wonder that a later Israelite could sing, “Happy is the man whose help is the God of Jacob!” (Ps. 146:5).

Israel: Man and Nation

The narratives of Genesis paint a vivid picture of Jacob’s character. His failings are recounted as much as his triumphs; he has a personality of his own, distinct from his relatives, distinct from any other ancient hero. Parallels may be found in folklore, legend, or history to one incident in his life or another, but they should all be recognized as common experience rather than cultural borrowings. The story of the patriarch’s progress is a consistent whole. The many incidental details and dissimilarities discredit theories that the stories are retrojections of events in the history of Israel the people.

That some similarities exist is obvious. Indeed, the ancient prophets realized this. Hosea applied to Israel the story of Jacob, for it was their story too (Hos. 12:2–4, 12 [MT 3–5, 13]). Less precise resemblance occurs between Jacob’s story and the teachings of Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Habakkuk concerning the faithful among the Israelites and the stages through which Jacob passed. Further exploration for “types” in Jacob’s sojourn in Haran or his “exile” in Egypt exceed the limits of reasonable exegesis. Malachi stressed the most important typical relation, the possession of the covenant, the distinction of the choice of God (Mal. 1:2). Later Jacob became an illustration and a type of the Church (Rom. 9:10–13).

References Outside Genesis

“Jacob” and “Israel” are the two names most frequently met with in the OT. In most cases these denote the children of Israel, particularly in the parallelism of poetic compositions. To this day the name of the patriarch is thus perpetuated. There remain, however, biblical passages that refer to Jacob himself.

In the Old Testament

A considerable group of verses associate him with Abraham and Isaac in naming God as the God of the fathers, underlining the continuity and the identity of the God of the past with the God of the present (e.g., Ex. 3:13–15). The collection of a small number of passages about the patriarch himself permits the reconstruction of a fairly complete epitome of his life. His birth as the younger twin, clutching his brother’s heel, is recounted by Hosea (12:3 [MT 4]). God’s choice of Jacob over Esau is mentioned in Malachi (1:2f), together with the inheritance of the covenant and all that it contained (Ps. 105:10f). Hosea tells specifically of the flight to Aram and the servitude by which Jacob gained his wife (12:12 [MT 13]). He is mentioned as the father of the twelve tribes (1 S. 12:8; 1 K. 18:31). His escape from Laban is probably referred to in Dt. 26:5, where a “Syrian ready to perish” (AV, RV) may be better translated “a fugitive Syrian” (RSV “a wandering Aramean”; NEB “a homeless Aramaean”; see A. R. Millard, JNES, 39 [1980], 153–55). The hand of God protected the small clan as it moved from place to place among hostile neighbors (Ps. 105:12–15), for the only land Jacob owned was the plot he had purchased near Shechem (Josh. 24:32). Hosea again summarizes the encounter at Peniel and the communion with God at Bethel (12:4 [MT 5]). The sale of Joseph as a slave to Egypt was God’s preparation for the future need of Jacob and his family when famine struck Canaan. So he was enabled to travel to Egypt and prosper there (Dt. 26:5; Josh. 24:4; Ps. 105:16–24). He died there, bequeathing the land at Shechem to Joseph’s sons (Josh. 24:32), who are counted as two of the tribes as if they had been Jacob’s own sons (Josh. 16–17). Here is evidence for the antiquity of the Jacob story and its diffusion, and it is noteworthy that all is consistent with the Genesis presentation. If the latter had been lost, it would still have been possible to write a biography of the father of the children of Israel.

In the New Testament

Four NT passages recall events in the life of Jacob. The conversation of Jesus (a descendant of the patriarch, Mt. 1:2; Lk. 3:33f) and the woman at the well of Sychar includes a declaration by the woman that Jacob provided the well (Jn. 4:12), besides the author’s note that this was the ground given by Jacob to Joseph (5:6). Samaritan pride can be felt in the woman’s words “our father Jacob.” Stephen mentions the famine and Jacob’s journey to Egypt in the course of his defense before the Sanhedrin (Acts 7:8–16). When the patriarch and his sons died in Egypt they were carried to Shechem and buried in the tomb Abraham bought from the sons of Hamor (vv 15f). This is one of the curious discrepancies in Stephen’s speech — the result, it is conjectured, of his endeavor to include all he could of Jewish history in his argument. For the apostle Paul, Jacob is an outstanding example of the sovereign choice of God, of the predestination of the elect (Rom. 9:10–13). The writer of Hebrews takes Jacob as one of his examples of active faith, a faith that acknowledges the present protection and worship of God and that can look forward fearlessly into the future (He. 11:9, 20–22).

From International Standard Bible Encyclopedia