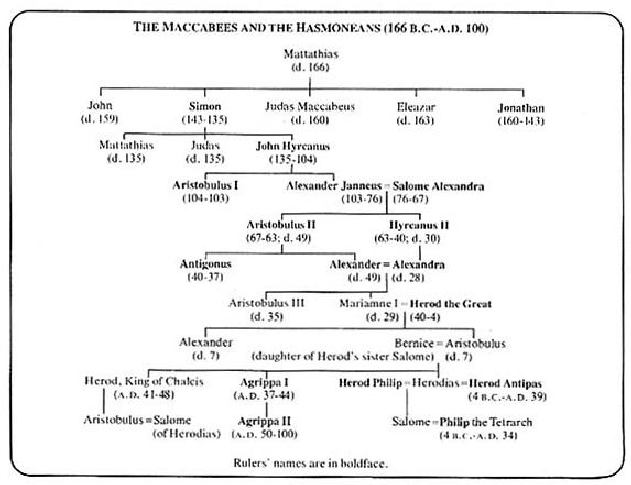

Hasmoneans hazʹme-nēʹenz [Gk Asamomaios; Heb ḥašmônay]. In the broader sense the term Hasmonean refers to the whole “Maccabean” family. According to Josephus (Ant. xii.6.1 [265]), Mattathias, the first of the family to revolt against Antiochus IV’s demands, was the great-grandson of Hashman. This name may have derived from the Heb ḥašmān, perhaps meaning “fruitfulness,” “wealthy.” Hashman was a priest of the family of Joarib (cf. 1 Macc. 2:1; 1 Ch. 24:7). The narrower sense of the term Hasmonean has reference to the time of Israel’s independence beginning with Simon, Mattathias’s last surviving son, who in 142 b.c. gained independence from the Syrian control, and ending with Simon’s great-grandson Hyrcanus II, who submitted to the Roman general Pompey in 63 b.c. Remnants of the Hasmoneans continued until a.d. 100.

I. Revolt of the Maccabees

The Hasmonean name does not occur in the books of Maccabees, but appears in Josephus several times (Ant. xi.4.8 [111]; xii.6.1 [265]; xiv.16.4 [490f]; xv.11.4 [403]; xvi.7.1 [187]; xvii.7.3 [162]; xx.8.11 [190]; 10.3 [238]; 10.5 [247, 249]; BJ i.7 [19]; 1.3 [36]; Vita 1 [2, 4]) and once in the Mishnah (Middoth i.6). These references include the whole Maccabean family beginning with Mattathias. In 166 b.c. Mattathias, the aged priest in Modein, refused to obey the order of Antiochus IV’s envoy to sacrifice to the heathen gods, and instead slew the envoy and a Jew who was about to comply. He then destroyed the altar and proclaimed, “Let every one who is zealous for the law and supports the covenant come out with me” (1 Macc. 2:15–27; Ant. xii.6.1–2 [265–272]; Dnl. 11:32–35). Mattathias and his five sons fled to the mountains. This marked the beginning of the Maccabean revolt. They waged war against the Jews who complied with Antiochus, tore down heathen altars, circumcised children who had been left uncircumcised, and exhorted all Jews to follow in their struggle. Mattathias died (166 b.c.) and left the crusade in the hands of his third son Judas, with whom a new era of fighting commenced (1 Macc. 2:42–70; Ant. xii.6.2–4 [273–286]).

Judas was very able and at Emmaus defeated the three generals sent by the Syrian regent Lysias and at Beth-zur defeated Lysias himself (1 Macc. 4:1–35; Ant. xii.7.4f [305–315]). Judas had regained the entire country and this allowed him to restore the worship in the temple in Jerusalem. On Chislev 25 (14 December, 164 b.c.), exactly three years after its desecration, the temple with its altar was rededicated and the daily sacrifices were reinstituted (1 Macc. 4:36–59; 2 Macc. 10:1–8; Ant. xii.7.6f [316–326]). This marked the commencement of the Jewish Feast of Dedication or Lights (Heb ḥanûkkâ).

Judas continued to fight Lysias. Finally in 163 b.c. Lysias had laid siege to Jerusalem. Because of adverse situations on both sides, Lysias and Judas made peace and guaranteed religious freedom for the Jews (1 Macc. 6:28–63). But Judas also wanted to have political freedom and continued in this struggle until his death at Eleasa in 160 b.c. (1 Macc. 7:14–9:22; Ant. xii.9.7–11.2 [384–434]). This brought disarray to Maccabean forces and the Hellenists were temporarily in control under the leadership of the Syrian general Bacchides.

Judas’s brother Jonathan continued the guerilla warfare against Hellenism. In 157 B.C. Jonathan’s defeat of Bacchides at Beth-basi (10 km [6 mi] S of Jerusalem) resulted in a peace treaty, and Bacchides returned to Antioch. This weakened the Hellenists and because of the internal struggles of Syria Jonathan gained strength for the next five years (1 Macc. 9:23–73; Ant. xiii.1.1–6 [1–34]). In 152 B.C. Syria had further internal struggles when Alexander Balas, who claimed to be the son of Antiochus IV, challenged the Seleucidian king Demetrius I. In 150 B.C.

Alexander Balas won and made Jonathan a general, governor, and high priest of Judah (the king of Syria selected the high priest but none had been chosen since the death of Alcimus in May, 159 b.c.) and considered Jonathan one of his chief friends (1 Macc. 10:22–66; Ant. xiii.2.3f [46–61]; 4.1f [80–85]). This was a strange combination: Alexander Balas, professed son of Antiochus Epiphanes, was in league with a Maccabean! Alexander Balas’s rule was challenged by Demetrius’s son, Demetrius II Nicator, in 147 b.c. and Balas was finally defeated in 145 b.c. Demetrius II confirmed Jonathan’s high priesthood and gave Jonathan the three districts of southern Samaria that he had requested. In 143 b.c. Demetrius II’s army rebelled, and Diodotus Tryphon (a general of Alexander Balas) claimed the Syrian throne for Alexander Balas’s son, Antiochus VI. Jonathan took advantage of the situation and sided with Tryphon, who in turn made Jonathan head of the civil and religious affairs and his brother Simon head of the military. Tryphon, however, fearful of Jonathan’s success, deceived him, arranged a meeting with him, and subsequently killed him (1 Macc. 10:67–13:30; Ant. xiii.4.3–6.6 [86-212]).

II. Rule of the Hasmoneans

A new phase of the Maccabean rule had emerged. Although the term “Hasmonean” is sometimes applied to the whole of the Maccabean family, it is more strictly applied to the high-priestly house, from the time of Simon to 63 b.c. The reason for this is that the Maccabean dream had finally come true, namely, that the Israelites had become politically and religiously an independent nation.

Judas had already achieved religious freedom, and Jonathan had become both the religious leader, by being appointed high priest, and the political leader, by becoming the sole ruler over Judea and by ousting the Hellenistic elements. Simon attempted and achieved complete independence from the Seleucid rule. This independence endured until Rome’s intervention in 63 b.c.

A. Simon (143–135b.c.)Simon, the second oldest son of Mattathias, succeeded his younger brother Jonathan. There was a great upheaval in Syria because Tryphon killed Antiochus VI and reigned in his stead as a rival to Demetrius II (1 Macc. 13:31f; Ant. xiii.7.1 [218–222]; Diodorus xxxiii.28.1; LivyEpit lv; Appian Syr 68; Justinus xxxvi.1.7). Because of the dastardly act of Tryphon against Simon’s brother, Simon naturally attached himself to Demetrius II on the condition of Judea’s complete independence. Since Demetrius II no longer controlled the southern parts of the Syrian empire, he extended to Simon complete exemption from past and future taxation. The significance of this is that the gentile yoke over Israel had been removed for the first time since the Babylonian Captivity, and Judea’s political independence meant that they could write their own documents and treaties. This was in 142 b.c. (1 Macc. 13:33–42; Ant. xiii.6.7 [213f]).

In order to insure the security of the new independent state, Simon took two actions. First, because of the possible threat of Tryphon, Demetrius II’s rival, Simon seized the fortress of Gazara (Gezer) between Jerusalem and Joppa, expelling the Gentiles and replacing them with Jews, and appointed his son John Hyrcanus as governor (1 Macc. 13:43–48, 53; 16:1, 21; Ant. xiii.6.7 [213–17]). Second, Simon shortly afterward captured the fortress of Acra in Jerusalem. Acra had never been in the hands of the Maccabeans but had been in the control of the hellenizers for more than forty years, serving as a reminder of the Syrian control. With the last vestige of Syrian control overthrown, the Acra was purified on the twenty-third day of the second month in 141 b.c. (3 June, 141 b.c.) (1 Macc. 13:49–52; Ant. xiii.6.7 [215–17]). Like his brothers Judas (1 Macc. 8:17) and Jonathan (1 Macc. 12:1), Simon made a peace treaty with Rome and Sparta, who guaranteed the freedom of worship.

In commemoration of Simon’s achievement, in 140 b.c. (Sept. 13) the Jews conferred upon him the position of leader and high priest forever until a faithful prophet should arise (1 Macc. 14:25–40, esp v 41). The high priesthood formerly belonged to the house of Onias but this had come to an end in 174 b.c. The Syrian kings had selected the intervening high priests, namely, Menelaus, Alcimus, and Jonathan. But now the Jews appointed Simon and his descendants as successors of the high priesthood. This marked the beginning of the Hasmonean dynasty, in that Simon and his successors had both the priestly and political power vested in their persons, and thus had far greater power than the political power of Judas and Jonathan or the religious power of the family of Onias.

In 139 b.c. Demetrius II was captured by the Parthians. In Demetrius II’s place his brother Antiochus VII Sidetes took up the struggle against Tryphon. He invited Simon’s help in his struggle against Tryphon by confirming to him all the rights and privileges already granted to him with the additional right to strike his own coins. Simon, however, refused the invitation. When Tryphon finally fled and committed suicide, Antiochus VII turned his attention to Simon. He accused Simon of unlawful expansion and demanded the surrender of Joppa, Gazara, and the Acra in Jerusalem along with tribute he received from the captured cities outside of Judea. If Simon refused these demands, he could pay an indemnity of one thousand talents. Simon refused to comply because he insisted that all these territories were rightly a part of Judea. Antiochus VII sent his general, Cendebeus, but was defeated by Simon’s two sons, Judas and John Hyrcanus (1 Macc. 15:1–14, 25–16:10; Ant. xiii.7.2f [223–27]; BJ i.2.2 [50–53]). This brought peace to Judea.

Finally, in 135 b.c. Simon and his two sons, Mattathias and Judas, were slain at a banquet near Jericho by his son-in-law Ptolemy, who had been appointed governor over the plain of Jericho but had ambitions for greater power. Ptolemy sent men to kill Simon’s second son, John Hyrcanus, at his residence in Gazara (where, also, he was the military governor). John, however, being warned of their coming, captured and killed them. John Hyrcanus went to Jerusalem and was well received (1 Macc. 16:11–23; Ant. xiii.7.4–8.1 [228–235]; BJ i.2.3f [54–60]).

Simon’s rule of eight years (Ant. xiii.7.4 [228]) had accomplished much for the Jews. He brought independence both politically and religiously. He had extended the boundaries of the nation, gained control over the land, and brought peace to the people whereby “each man sat under his vine and his fig tree, and there was none to make them afraid” (1 Macc. 14:4–15).

B. John Hyrcanus (135–104b.c.)John Hyrcanus succeeded his father as high priest and ruler of the people. In the first year of his reign he had trouble because Antiochus VII, who had failed to take over Judea under Simon, asserted his claim of ruler over Judea, seized Joppa and Gazara, ravaged the land, and finally besieged Jerusalem for more than a year. With food supplies dwindling, Hyrcanus asked for a seven-day truce in order to celebrate the Feast of Tabernacles. Antiochus not only complied but also sent gifts to help them in their celebration. This action indicated Antiochus’s willingness to negotiate a peace settlement. The result was that the Jews had to hand over their arms; pay heavy tribute for capture and possession of Joppa and other cities bordering on Judea; and give hostages, one of whom was Hyrcanus’s brother. The walls of Jerusalem were destroyed, but the Syrians could not establish a garrison in Jerusalem (Ant. xiii.7.4–8.3 [228–248]; BJ i.2.5 [61]). The independence won by Jonathan and Simon was destroyed by a single blow, though only because Syria could concentrate its efforts. In 130 b.c., however, Antiochus VII became involved in a campaign against the Parthians that resulted in his death in 129 b.c. Demetrius II, released by the Parthians, again gained control of Syria (129–125 b.c.), but because of the troubles within Syria Demetrius II was unable to bother Hyrcanus. Hyrcanus renewed the alliance with Rome whereby Rome confirmed his independence and warned Syria against any incursion into Hyrcanus’s territory. Also, Hyrcanus’s payment of indemnity for Joppa and other cities ceased. The long struggle between the Hasmoneans and the Seleucids came to an end (Ant. xiii.9.2 [259–266]). Hyrcanus took advantage of the situation and extended his borders to the east by conquering Medeba in Transjordan, to the north by capturing Shechem and Mt. Gerizim and by destroying the Samaritan temple at Mt. Gerizim (128 b.c.), and to the south by taking over the Idumean cities of Adora and Marisa, where he forced the Idumeans to be circumcised and to obey the Jewish law or emigrate (Ant. xiii.8.4–9.1 [249–258]; BJ i.2.6f [62-66]). Later in 109 b.c. Hyrcanus and his sons conquered Samaria and thus were able to occupy the Esdraelon Valley all the way up to Mt. Carmel (Ant. xiii.10.2f [275-283]; BJ i.2.7 [64–66]), Hyrcanus’s independence was further demonstrated by the minting of coins bearing his own name, an unprecedented action for a Jewish king (110/109 b.c.).

With Hyrcanus’s successes came a rift between him and the Pharisees. Although the origins of the Pharisees and the Sadducees are somewhat obscure, they were well established and influential by the time of Hyrcanus’s reign. The Pharisees, who were descendants of the Hasideans, were somewhat indifferent to the political success of the Hasmoneans and felt that the high priesthood had become worldly by hellenization and secularization. Hence they questioned whether Hyrcanus should be the high priest. The Sadducees, however, a party of mostly wealthy priestly aristocracy, were antagonistic toward the Pharisees and sided with Hyrcanus. Consequently, Hyrcanus joined in with the Sadducees. This indicates both the thinking of the Sadducees and the decline of the office of the high priest (Ant. xiii.10.5f [288–296]; TB Berakhoth 29a).

After thirty-one years of rule Hyrcanus died peacefully (104 b.c.), leaving five sons (Ant. xiii.10.7 [299f]; BJ i.2.8 [67–69]).

C. Aristobulus I (104–103b.c.)Hyrcanus desired that his wife would head the civil government while his oldest son Aristobulus I would be the high priest. Displeased with this, Aristobulus imprisoned all his brothers except Antigonus, who shared in ruling until Aristobulus became suspicious and had him killed. Aristobulus’s rule lasted only a year, but he was able to conquer Galilee, whose inhabitants he compelled to be circumcised. Aristobulus died of a severe illness (Ant. xiii.11.1–3 [301–319]; BJ i.3.1–6 [70–84]).

D. Alexander Janneus (103–76b.c.)On the death of Aristobulus, his wife Salome Alexandra released his three brothers, one of whom was Alexander Janneus, from prison. She appointed him as king and high priest and subsequently married him, though he was thirteen years her junior (Ant. xiii.12.1 [320–24]; BJ i.4.1 [85]), This marriage was against the law, for the high priest was to marry only a virgin (Lev. 21:13f). Alexander Janneus endeavored to follow in the footsteps of his father and brother in territorial expansion. He captured the coastal Greek cities from Carmel to Gaza (except Ascalon), compelling the inhabitants to follow the Jewish law. He was successful in his conquests in Transjordan and the south, so that the size of his kingdom was equal to that of David and Solomon (Ant. xiii.12.2–13.4 [324-371]; BJ i.4.2 [86f]).

There were, however, real conflicts within his domain. The Pharisees saw that the Hasmoneans were deviating more from their ideals, for Alexander Janneus was a drunkard who loved war and was allied with the Sadducees. Tension came to a head at a celebration of the Feast of Tabernacles when Alexander Janneus poured the water libation over his feet instead of on the altar as prescribed by the Pharisaic ritual. The people, enraged, shouted and pelted him with lemons. Alexander ordered his mercenary troop to attack, and six thousand Jews were massacred (Ant. xiii.13.5 [372–74]; BJ i.4.3 [88f]; TB Sukkah 48b). This act brought great bitterness, and the people awaited an opportunity for revenge.

The time came in 94 b.c. when Alexander Janneus attacked Obedas king of the Arabs, but suffered a severe defeat and barely escaped with his life. Upon his return to Jerusalem the people turned against him; with the help of foreign mercenaries Alexander Janneus fought six years against his people, slaying no less than fifty thousand Jews. The Pharisees finally in 88 b.c. called upon the Seleucid Demetrius III Eukairos to help them. Wars bring strange allies, for the descendants of the Hasideans asked the descendants of Antiochus Epiphanes to aid them in their fight against the descendants of the Maccabees! Alexander Janneus was defeated at Shechem and fled to the mountains. Six thousand Jews, however, realizing that their national existence was threatened, sided with Alexander Janneus because they felt it the lesser of two evils to side with him in a free Jewish state than to be annexed to the Syrian empire. But when Alexander Janneus reestablished himself, he forced Demetrius to withdraw, and he ordered eight hundred Pharisees to be crucified and their wives and children to be killed before their eyes while he was feasting and carousing with his concubines. Because of these atrocities eight thousand Jews fled the country (Ant. xiii.13.5–14.2 [375-383]; BJ i.4.4–6 [90–98]).

After this there were upheavals in the Seleucid empire that affected Alexander Janneus. The Nabateans were becoming strong and opposed a Seleucid rule. Around 85 b.c. the Nabatean king Aretas invaded Judea, and Alexander Janneus retreated to Adida (32 km. [20 mi] NW of Jerusalem), but Aretas withdrew after coming to terms with Janneus. From 83 to 80 b.c. he was successful in his campaign in the east, conquering Pella, Dium, Gerasa, Gaulana, Seleucia, and Gamala. The last three years of his life (79–76 b.c.) he contracted an illness due to his overdrinking, and when he died he was buried with great pomp (Ant. xiii.14.3–16.1 [384-406]; BJ i.4.7f [99–106]).

E. Salome Alexandra (76–67b.c.)On his deathbed, Alexander Janneus appointed his wife, Salome Alexandra, as his successor. Because the Law barred a woman from the priesthood, Salome selected her oldest son Hyrcanus II as the high priest. This did not please her younger son Aristobulus II, who was ambitious for power. Alexander Janneus also advised his wife to make peace with the Pharisees since they controlled the mass of the people. She followed his advice and this marked the revival of the Pharisaic influence. This change was not difficult since her brother, Simeon ben Shetah, was the leader of the Pharisees. It soon became obvious that though she had the title, the Pharisees were really the power behind the throne. The Pharisees reintroduced Pharisaic legislation that had been abandoned by John Hyrcanus a few years earlier. Also, the Pharisees sought revenge for the slaughter of the eight hundred Pharisees, their wives, and their children during Alexander Janneus’s reign, and thus put to death some of those who had advised Alexander Janneus in this atrocity. The Sadducees, who saw that as an attack on them, sent a delegation to Alexandra to protest this revenge. One of the delegates was her son Aristobulus II, who openly sided with the Sadducees against the Pharisees. With Alexandra’s permission, the Sadducees were allowed to leave Jerusalem and to take control of several fortresses in various areas of the land. With Aristobulus II as their military leader, Hyrcanus II complained to Alexandra of Aristobulus’s strength. When Alexandra became sick, Aristobulus II realized that he must win support if he, rather than Hyrcanus II, were to gain the throne. Aristobulus II left Jerusalem to enlist support of the surrounding cities, and within fifteen days he had the support of most of the country and control of twenty-two fortresses. Hyrcanus II and his advisers became alarmed and sought Alexandra’s advice. She wanted Hyrcanus II to succeed her, but before anything could be done she died. Her reign was marked with peace both at home and abroad, except for the family turmoil (Ant. xiii.15.6–16.6 [399–432]); BJ i.5.1–4 [107–119]).

F. Aristobulus II (67–63b.c.)With Alexandra’s death Hyrcanus II assumed the positions of king and high priest. This, however, was short-lived, for Aristobulus II declared war on him. With many of Hyrcanus II’s soldiers deserting him, Hyrcanus II fled to Jerusalem’s citadel (later known as Fortress Antonia) and finally was forced to surrender. The two brothers agreed that Hyrcanus II was to relinquish his positions as king and high priest to Aristobulus II and to retire from public life and that Aristobulus II was to leave Hyrcanus II’s revenue undisturbed. Hyrcanus II ruled for only three months.

Hyrcanus II was willing to accept this, but the Idumean Antipater II (the son of Antipater I, who had been appointed governor of Idumea by Alexander Janneus, and the father of Herod the Great) had other plans for him. Antipater realized that Hyrcanus II was a weak and idle man and that he could control him. Yet he himself could not be the high priest because he was an Idumean. Antipater convinced Hyrcanus II that Aristobulus unlawfully took the throne and that Hyrcanus II was the legitimate king. Furthermore, he convinced him that Hyrcanus II’s life was in danger, and so he traveled by night from Jerusalem to Petra, the capital of Edom. Aretas was willing to help Hyrcanus II on the condition that he would give up the twelve cities of Moab taken by Alexander Janneus. Hyrcanus and Aretas having agreed, Aretas attacked Aristobulus II, who was defeated and retreated to the temple mount at the time of Passover in 65 b.c. Many people sided with Hyrcanus II (Ant. xiv.1.2–2.2 [4-28]; BJ i.6.1f [120–26]; cf. also Justin Martyr Dial lii; Eusebius HE i.6.2; 7.11; TB Baba Bathra 3b–4a; Kiddushin 70a).

Meanwhile the Roman army under Pompey was moving through Asia Minor after defeating Mithridates in 66 b.c. Pompey sent Scaurus to Syria, and upon his arrival at Damascus he heard of the dispute between the two brothers. When he had hardly arrived in Judea, both brothers sent emissaries asking for support. Aristobulus II offered four hundred talents, and Hyrcanus II followed suit, but Scaurus accepted Aristobulus II, for he felt he would be able to pay. He commanded Aretas to withdraw or else be declared an enemy of Rome. He pursued Aretas, inflicting a crushing defeat, and then returned to Damascus. Shortly after, Pompey arrived in Damascus, and three envoys approached him: one from Hyrcanus II who complained that Aristobulus II seized the power unlawfully; a second from Aristobulus II who claimed he was justified in his actions and that his brother was incompetent to rule; and a third from the Pharisaic element who asked for the abolition of the Hasmonean rule and the restoration of the high-priestly rule. Pompey wanted to delay his decision until after the Nabatean campaign.

Aristobulus II, displeased with this, quit fighting for Pompey against the Nabateans. Pompey dropped the Nabatean expedition and went after Aristobulus II. Aristobulus II lost heart and Pompey asked for the surrender of Jerusalem in exchange for Pompey’s dropping his hostilities. Pompey’s general Gabinius was sent to Jerusalem but was barred from the city. Pompey was outraged and attacked the city. Within the city Aristobulus II’s followers wanted to defend themselves while Hyrcanus II’s followers wanted Pompey as an ally and wanted to open the gates. Because the majority were with Hyrcanus II, the gates were opened, but Aristobulus II’s men held out at the temple mount. After a three-month siege, Pompey entered the temple mount, and twelve thousand Jews were killed (autumn of 63 b.c.). Pompey entered the holy of holies, but he did not disturb it. In fact, on the following day he gave orders for cleansing it and for resuming the sacrifices there. Hyrcanus II was reinstated as high priest, and Aristobulus II, his two daughters and two sons, Alexander and Antigonus, were taken to Rome as prisoners of war. Alexander escaped. In the triumphal parade in 61 b.c. Aristobulus II was made to walk before Pompey’s chariot.

This marked the end of the seventy-nine years (142–63 b.c.) of independence of the Jewish nation as well as the end of the Hasmonean house. Hyrcanus II, the high priest, was merely a vassal of the Roman empire (Ant. xiv.2.3–4.5 [29-79]; BJ i.6.3–7.7 [128-158]; Tacitus Hist. v.9; Appian Mithridactic Wars 106, 114; Florus i.40.30; Livy 102; Plutarch Pompey xxxix; cf. Dio Cassius xxxvii.15–17).

III. Demise of the Hasmoneans

The loss of independence brought about the decline of the Hasmoneans. Their power was weakened and what power they had was gradually being transferred to the Herods (See Herod).

A. Hyrcanus II (63–40b.c.).Although Hyrcanus II was reappointed high priest, Antipater was the power behind the throne who was responsible for Hyrcanus II’s position and honor. Antipater proved himself useful to the Romans in government. On the other hand, the Romans helped Antipater quell troubles caused by some of the Hasmoneans. Aristobulus II’s family bitterly resented Rome’s favoring Hyrcanus II over his brother Aristobulus II, and they made attempts to regain his status of high priest and political ruler. In 57 b.c., while Alexander (son of Aristobulus II), a Roman prisoner, was being taken to Rome, he escaped and succeeded in collecting an army of ten thousand heavily armed soldiers and one thousand four hundred horsemen, but he was finally defeated by Gabinius, the new Roman governor of Syria, and Mark Antony. In 56 b.c. Aristobulus II and his other son Antigonus escaped from their Roman imprisonment and caused a revolt in Judea, but a Roman detachment attacked his little band and they were driven across the Jordan. Although attempting to defend themselves in Machaerus, Aristobulus II and Antigonus had to yield after two days and they were again sent to Rome as prisoners. The Roman Senate decided to keep Aristobulus II in prison but released his two sons, Alexander and Antigonus, because of their mother’s helpfulness toward Gabinius. They returned to Judea. In 55 b.c. Alexander revolted again and won many people to his side, but this was quickly brought to an end. Gabinius then went to Jerusalem and reorganized the government according to Antipater’s wishes (Ant. xiv.5.1–6.1 [80-97]; BJ i.8.2–7 [160-178]; Dio Cassius xxxix.56; Plutarch Antony iii).

Antipater married a woman named Cypros, of an illustrious Arabian family, by whom he had four sons — Phasael, Herod, Joseph, Pheroras — and a daughter, Salome (Ant. xiv.7.3 [121]; BJ i.8.9 [181]).

When Julius Caesar became ruler of Rome in 49 b.c., Pompey and the party of the Roman Senate fled from Italy. This left Antipater and Hyrcanus II in the precarious situation of possibly being unable to handle revolts. In fact, Caesar released the imprisoned Aristobulus II and gave him two legions to fight the party of Pompey in Antioch and finally take control of Syria and Judea. But before he could leave Rome, Aristobulus II was poisoned by friends of Pompey. In addition, Aristobulus II’ s son, Alexander, who sided with Caesar, was beheaded at Antioch by order of Pompey. This means that only Antigonus, the other son of Aristobulus II, remained as a threat to Hyrcanus II and Antipater (Ant. xiv.7.4 [123–25]; BJ i.9.1f [183–86]; Dio Cassius xli.18.1).

When Julius Caesar defeated Pompey in Egypt in 48 b.c., Hyrcanus and Antipater attached themselves to the victor. Caesar made Antipater a Roman citizen with exemption from taxes. He appointed him procurator of Judea and reconfirmed Hyrcanus II’s high priesthood. He also gave Hyrcanus the title of Ethnarch of the Jews (Ant. xiv.8.1–5 [127–155]; 10.2 [191]; BJ i.9.3–10.4 [187-203]). Immediately after, Antipater went about the country to suppress disorder and appealed to the restless Judean population to be loyal to Hyrcanus II. In essence, however, Antipater was ruling, and it was he who appointed his son Phasael as the governor of Jerusalem and his second son Herod as governor of Galilee in 47 b.c. (Ant. xiv.9.1f [156-58]; BJ i.l0.4 [201–203]). Herod was successful in ridding Galilee of bandits.

In 47 b.c. or early 46 b.c., some Jews complained to Hyrcanus II that Herod was becoming too powerful and that he had violated the Jewish law and consequently should be tried before the Sanhedrin. So Hyrcanus II ordered Herod to a trial. Herod came to the trial, not appearing as an accused person, but as a king, decked in purple and attended by a bodyguard. Sextus Caesar, the new governor of Syria, ordered Hyrcanus II to acquit Herod or serious consequences would follow. Herod was released and fled to join Sextus Caesar at Damascus. Sextus appointed Herod as governor of Coelesyria because of his popularity and thus Herod became involved with the affairs of Rome in Syria. Herod began to march against Jerusalem in order to avenge himself for the insult Hyrcanus II had directed toward him, but was persuaded by his father and brother to abstain from violence (Ant. xiv.9.3–5 [163–184]; BJ i.10.6–9 [208–215]; cf. TB Kiddushin 43a).

After Cassius, Brutus, and their followers murdered Julius Caesar in 44 b.c., Cassius came to Syria. Needing to raise certain taxes required by Cassius, Antipater selected Herod, Phasael, and Malichus for the job. Herod was very successful in this, and Cassius appointed him governor of Coelesyria (as he had been under Sextus Caesar). Since the Herods were gaining strength, Malichus, whose life Antipater had previously saved, bribed the butler to poison Antipater. Herod killed Malichus (Ant. xiv.11.3–6 [277–293]; BJ i.11.2–8 [220–235]).

Herod was growing in power but was not always liked by the Jews because he was an Idumean. Although he was married to Doris, who was probably Idumean also, he became betrothed to Mariamne, who was the granddaughter of Hyrcanus II (her mother was Alexandra) and the daughter of Aristobulus II’s son, Alexander, and thus a niece to Antigonus, the rival of Herod (Ant. xiv.12.1 [300]; BJ i.12.3 [241]). This strengthened Herod’s position immensely, for he would marry into the royal house of the Hasmoneans and would become the natural regent when Hyrcanus II, who was growing old, passed away.

In 42 b.c. when Antony defeated Cassius, the Jewish leaders accused Herod and Phasael of usurping the power of the government while leaving Hyrcanus II with titular honors. Herod’s defense nullified these charges (Ant. xiv.12.2–6 [301–323]; BJ i.12.4–6 [242–45]; Plutarch Antony xxiv; Dio Cassius xlviii.24; Appian Civil Wars v.4). Since Hyrcanus II was there, Antony asked him who would be the best qualified ruler, and Hyrcanus II chose Herod and Phasael. Antony appointed them as tetrarchs of Judea (BJ i.12.5 [243f]; Ant. xiv.13.1 [324–26]).

B. Antigonus (40–37b.c.)The next year (40 b.c.) the Parthians appeared in Syria. They joined Antigonus in the effort to remove Hyrcanus II. After several skirmishes, the Parthians asked for peace. Phasael and Hyrcanus II went to Galilee to meet the Parthian king while Herod remained in Jerusalem, suspicious of the proposal. The Parthians treacherously put Phasael and Hyrcanus II in chains, and Herod with his close relatives, Mariamne, and his troops moved to Masada and then to Petra (Ant. xiv.13.3–9 [335–364]; BJ i.13.2–9 [250–264]). Antigonus was made king (Dio Cassius; xlviii.41; inferred in Ant. xiv.13.10 [368f]; BJ i.13.9 [268–270]; cf. also Dio Cassius xlviii.26). In order to prevent the possibility of Hyrcanus II’s restoration to high priesthood, Antigonus mutilated him. Phasael died either of suicide or poisoning (Ant. xiv.l3.10 [367–69]; BJ i.13.10f [271–73]). Hyrcanus II was taken to Parthia (Ant. xv.2.1 [12]).

Herod went to Rome where Antony, Octavius Caesar, and the Senate designated him King of Judea (Ant. xiv.14.6 [381–85]; BJ i.14.4 [282–85]; cf. also Strabo Geog. xvi.2.46; Appian Civil Wars v.75; Tacitus Hist v.9). In late 40 or early 39 b.c. Herod returned to Palestine, and with the help of Antony’s legate Sossius, was able to recapture Galilee. In the spring of 37 b.c. he prepared for the siege of Jerusalem. While assigning his army several duties he left for Samaria to marry Mariamne to whom he had been betrothed for about five years. This was a contemptuous act against Antigonus, the uncle or Mariamne, for her being a Hasmonean strengthened Herod’s right to the throne. After the wedding he returned to Jerusalem, which fell in the summer of 37 after a long and bitter struggle (Ant. xiv.15.8–16.2 [439-480]; BJ i.16.7–18.2 [320-352]; Tacitus Hist v.9; Dio Cassius xlix.22). At Herod’s request, the Romans beheaded Antigonus (BJ i.18.3 [357]; Plutarch Antony xxxvi; cf. also Dio Cassius xlix.22), which meant the end of the Hasmonean rule. Herod, therefore, ceased to be the nominee for king and became king de facto.

C. Mariamne and Her Sons (37–7b.c.).One of the first moves Herod made as king was to appoint Ananel (Hananeel), who was of the Aaronic line, as high priest to replace Hyrcanus II who, although just returning from the Parthian exile, was disqualified because Antigonus had mutilated him (Ant. xv.2.1–4 [11–22]). Herod chose a priest who had no influence. Alexandra, who was Herod’s mother-in-law as well as Hyrcanus II’s daughter, was infuriated by his choice of a priest outside the Hasmonean line, especially because he overlooked her own sixteen- year-old son, Aristobulus III, the brother of Herod’s wife Mariamne. Finally, Alexandra, with Cleopatra’s pressure upon Antony, forced Herod to set aside Ananel (which was unlawful because a high priest was to hold the office for life) and make Aristobulus III high priest when he was only seventeen years old (late 36 or early 35 b.c.). Because of Aristobulus III’s growing popularity, Herod managed to have him accidentally drowned in a swimming pool at Jericho right after the Feast of Tabernacles. Herod arranged for an elaborate funeral. Although the people never questioned the official verisons, Alexandra believed that her son had been murdered. She reported this to Cleopatra, who persuaded Antony to summon Herod for an account of his actions. Realizing that his life was in danger, Herod put his wife Mariamne under surveillance and secretly instructed those in charge to kill Mariamne if he were killed so that she would not become someone else’s lover. By eloquence and bribery, Herod persuaded Antony to free him of any charges. Upon his return in 34 b.c. Herod realized that Mariamne found out about his plan to kill her, but he also heard the charge that she had an affair with the one who was to watch her while he was away. She denied the charge, and after some debate they were reconciled. Herod surmised that some of the troubles were caused by her mother Alexandra, so he put her in chains and under guard (Ant. xv.2.5–3.9 [23-87]; BJ i.22.2–5 [437–444]).

Antony was defeated by Octavius in the Battle of Actium on 2 September, 31 b.c. Herod, in the spring of 30 b.c., went to Rhodes to meet Octavius and convince him that he was loyal. Before Herod left for Rhodes, he sentenced and executed Hyrcanus II, the only remaining rival claimant to the throne. Also, he had Mariamne and her mother Alexandra placed under observation and instructed two guards to execute them if he did not return from Rhodes. At their meeting in Rhodes in the spring of 30 b.c., Octavius was convinced of Herod’s loyalty and confirmed his royal rank (Ant. xv.5.1–6.7 [108-201]; BJ i.19.3–20.3 [369–395]).

While Herod was at Rhodes, however, Mariamne found out from the two guards that she was to be killed in the event that he did not return. This caused an intense situation for Herod, and after a complicated series of events, he condemned and finally executed Mariamne at the end of 29 b.c. (Ant. xv.7.1–5 [202–236]). But Herod never accepted Mariamne’s death. He fell ill, and because his recovery was doubtful, Alexandra tried to win over two fortified places in Jerusalem so that she could secure the throne. When Herod heard of this plot, he had her executed in 28 b.c. (Ant. xv.7.6–8 [237–252]). Finally, the governor of Idumea, Costobarus (husband of Herod’s sister Salome), who had earlier conspired with Cleopatra against Herod, once again came under suspicion for alleged pro-Hasmonean sympathies. Herod killed Costobarus and his followers, the influential sons of Babas, who remained loyal to Antigonus. Herod now could console himself that all of the male relatives of Hyrcanus II (who could dispute the occupancy of the throne) were no longer living (Ant. xv.7.9f [253-266]).

The only Hasmoneans who would claim the throne were Herod’s own sons by Mariamne. She bore him five children. The two daughters were Salampsio and Cypros (Ant. xviii.5.4 [130–32]). The youngest son died during the course of his education in Rome (BJ i.22.2 [435]). The older sons were Alexander and Aristobulus (Ant. xvi.4.6 [133]; xvii.5.4 [134]). Herod made out a will in 22 b.c. that would make these two sons his successors. Both of these sons had no real fondness for their father, for he had killed their mother. When Herod heard and believed the rumors that these two sons planned to kill him to avenge their mother’s death, he made out a new will in 13 b.c. declaring Antipater, son of his first wife Doris, the sole heir (BJ i.23.2 [451]). Antipater realized that Herod could again change his mind about the will, so he repeatedly wrote letters from Rome, kindling his father’s anger against Alexander and Aristobulus and ingratiating himself. Finally, in Italy in 12 b.c., Herod brought Alexander and Aristobulus to trial before Augustus to prove that they were not worthy of the throne. The outcome of the trial, however, was reconciliation, and when they returned home Herod made out his third will, naming Antipater as his first successor and after him Alexander and Aristobulus (Ant. xvi.3.1–4.6 [66-135]; BJ i.23.1–5 [445–466]).

Scarcely had they arrived home when Antipater, being helped by Herod’s sister Salome and Herod’s brother Pheroras, began to slander the two sons of Mariamne. Alexander and Aristobulus became decidedly more hostile in their attitude, Herod became more morbid about the situation, and Antipater played on Herod’s morbid fears. Although there was a reconciliation in 10 b.c., finally in 7 b.c. with Augustus’s instruction his sons were tried at Berytus (Beirut) and found guilty. Herod had Alexander and Aristobulus executed by strangulation at Sebaste, where he had married their mother thirty years before (Ant. xvi.8.1–11.8 [229-404]; BJ i.24.7–27.6 [488-551]).

The remaining Hasmonean influence came after Herod’s death. Aristobulus had married Bernice, the daughter of Herod’s sister Salome, and they had three notable children (BJ i.28.1 [552f]). First, there was Herod who was king of Chalcis from a.d. 41 to 48. Second, there was Herod Agrippa I who was king of the Jews from a.d. 37 to 44 (Acts 12), being succeeded by his son Herod Agrippa II, who was king of the Jews from a.d. 50 to 100 (Acts 25–26). Third, there was Herodias who married Herod Antipas, who ruled as tetrarch over Galilee and Perea from 4 b.c. to a.d. 39 (Mt. 14:3–12; Mk. 6:17–29; Lk. 3:1, 19f; 13:31–33; 23:6–12). Herodias had a daughter, Salome, from a previous marriage, who married Herod Antipas’s brother, Philip the tetrarch (Lk. 3:1).

Bibliography.—E.R. Bevan, The House of Seleucus (1902); Jerusalem under the High-Priests (1904), pp. 100–162; CAH, VIII (1930), 495–533; IX (1932), 397–417; E. Bickerman, From Ezra to the Last of the Maccabees (1947), pp. 136–182; S. Tedesche and S. Zeitlin, First Book of Maccabees (1950); J. C. Dancy, comm on I Maccabees (1954); V. Tcherikover, Hellenistic Civilization and the Jews (1959), pp. 235–265, 403f; S. Zeitlin, Rise and Fall of the Judaean State, I (1962), 141–201, 317–411; D. S. Russell, The Jews from Alexander to Herod (1967), pp. 57–102; B. Reicke, New Testament Era (Engtr 1968), pp. 63–107; Y. Aharoni and M. AviYonah, Macmillan Bible Atlas (1968), pp. 129–139; J. R. Bartlett, First and Second Books of the Maccabees (CBC, 1973); E. Schürer, HJP2, I, 189–242, 267–286.

H. W. Hoehner